The recent game between the Bruins and the Penguins highlights the shortcomings of the NHL's discipline system. It's hard to say how effective it has been since it was instituted after Matt Cooke ended Marc Savard's career. I honestly don't watch enough games to keep track of things, but, there doesn't seem to be many fewer hits to the head than there were before the system was established. Or even if the incidents have decreased, that decrease might be entirely from Matt Cooke no longer routinely hitting people in the head. Which I guess is something. But there is still a lot of dangerous plays happening and there is way too much confusion and ambiguity around how to punish these plays. Luckily, a bookish intellectual living in Somerville is here to save the NHL. Here's how I would fix the NHL's Discipline problem.

Systematize the Suspension System: Right now, a player gets suspended for as long as Brendan Shannahan says he gets suspended. Whether it's fair or not to criticize Shannahan's judgment—wait, no, it is. Far too often, Shannahan makes his decision based on story lines and public relations. If it looks really bad, you get a long suspension. If it doesn't look too bad, no matter how dangerous the play was, you might not get a suspension. And if you're a star player in the playoffs like Shea Weber you might not get suspended at all. (Just a fine.) This is not just a problem with Shannahan, but a problem with human judgment. There will always be an element of judgment in anything like this, but the more we can minimize it, the fairer and more effective the discipline system will be. How would the system work? The NHL would establish classes of dangerous plays. For example, a flow-of-play, on-the-puck dangerous play might be a Class C infraction, like if, in going for a legal hit, a player's arms, elbows, or shoulder, unintentionally made significant contact with an opponent's head, would carry a 2-game suspension for the first offense, and then additional games for each additional offense after that. These classes can make distinctions between (and should certainly include) plays involving sticks, fists, shoulders, and elbows, as well as plays targeting the upper or lower body. (Lower body stuff in particular is being neglected I think, especially given how many fights start with one player taking a shot at an opponent's knees.) This system doesn't have to be massively complex, just give enough structure that it is not always the responsibility of a human judge to assess the discipline.

Render the Fact of Injury Irrelevant: For the most part, a player can engage in a wildly dangerous play and get away without punishment if the opponent is not injured. I think we all know that if Marchand had gone off on the stretcher we would all be talking about Neal's knee to the head as one of the dirtiest plays of the last few years. If the play is dangerous, it's dangerous and that's it, and that fact needs to be formalized in order for discipline to be a meaningful deterrent to dangerous plays. Does this mean someone could end up with a 10-game suspension for a play in which his opponent was totally unhurt? Yes. But the goal of the discipline system is not to punish injurious plays but to prevent dangerous plays. That said, I would be totally cool with formalizing some kind of “severity” extra consideration. For example, if the league wants to add a greater penalty to a play because they believe it was an unusually severe example of the dangerous play, I think it would be fair to include the fact of injury as evidence in their case for the extra punishment, but not as proof for the extra punishment.

Formalize the Benefit of the Doubt: What was the difference between Orpik's unpenalized hit and Seidenberg's penalized hit? The benefit of the doubt. Essentially, the referees gave Orpik the benefit of the doubt; that he'd committed to the hit before the strange puck bounce off the boards put Erikson in a dangerous position and his target was Erikson's chest, even though there was substantial contact with the head. They assumed he was making a good hockey play, and the responsibility for the injury Erikson suffered, rested in the nature of hockey and an unlucky bounce. Seidenberg was not given the benefit of the doubt on his check. The result is that no one is really sure what constitutes an illegal hit to the head, which means that, if you've got a chance to really deck a guy, it might still be worth the risk. One way or the other, the league needs to formalize the benefit of the doubt and write into the rules something like, “If the referee is unsure whether an illegal hit to the head occurred he should assess the penalty.” Or not assess the penalty. The important thing is that everyone knows that if the play is borderline, as most plays are, it will be called the same way in every game and every situation.

Reform the Instigator Penalty: (Yeah, I've harped about this before, but it's relevant.) I don't know if fighting deters dangerous plays. I don't think anyone knows for sure one way or the other. But enough people, with all different relationships with the game, believe the idea that it is going to stick around for the foreseeable future. However, the structure of the instigator penalty compromises whatever ability fighting may have as a deterrent. A player who decides to engage in a dangerous play, knows that there is an extra deterrent against coming after him. However, I don't think we should get rid of the instigator role entirely. Too many fights are started after perfectly legal hits. Here's how I'd change things. After a fight, if the referees believed there was an instigator to that fight, they would formally label that player an “instigator.” After the game, the league would review run of play preceding the fight. If they believe there were no dangerous plays, the “instigator” is suspended for one game (and an additional game for each additional time he is an “instigator”). If they find a dangerous play, that player is not assessed the suspension. If the dangerous play they do find, fits one of the classes of suspension, that player is suspended under those rules. In this way, players are punished, both for unnecessary fights and for dangerous plays. (Sidenote: I don't entirely understand why a society perfectly cool with MMA and boxing has a problem with institutionalized fighting in hockey. That's not an endorsement of fighting in hockey. I honestly don't really know how I feel about it, but it does strike me as a tad incongruous.)

There is a chance that hockey (and football) is coming to a crisis point. The players are now moving so fast and are now so big and strong that plays that were safe for decades are now dangerous. To put this another way, our skulls haven't gotten any thicker even as the rest of our bodies have gotten bigger and stronger. Which, of course, brings about some of the most difficult questions around the nature of sport. How much risk is justified for our entertainment? What do we do about youth sports where, by definition, the kids playing are not responsible for their own well-being? When do the dangers of sport overtake the joys and whose joys have precedence? I honestly, hope we don't end up needing to ask these questions, but unless the discipline system is fixed, we will.

Friday, December 13, 2013

Tuesday, December 3, 2013

Biggest Bang for Your Local Buck

If you’re reading this blog, I’m going to assume you know all of the economic benefits of shopping with locally owned businesses. (If you don’t here’s a post I did for the bookstore with lots of data.) Executive summary: Karma wheel, it all comes back to you. Or to put this a different way; profitable locally owned businesses are good for the locales in which they are owned and operated. The more profitable they are, the more they can donate, the more taxes they pay, and the higher the employees salary, all of which is good for you. I'm also going to assume that you're not an eccentric millionaire and that you want to do as much as you can, within your means, to contribute to your community. Here are some ways to amplify the economic benefits of your local spending, without actually spending any more money.

Pay in Cash: Credit cards are convenient, but that convenience comes at a cost. Some of it is interest payments and customer fees, but much of that cost is paid by the stores themselves in the form of merchant or vendor fees. (This is not a knock on it, but if you've ever wondered what's in it for American Express with the whole Small Business Saturday thing, this is it.) In the long term, these fees lead to more expensive stuff, as the fees are built into the cost of goods, and in the short term they can be a major burden on small businesses. After staffing, credit card processing fees tend to be the next biggest single non-discretionary expense. There are no fees for cash, of course. Cash, though, takes some planning ahead. At PSB at least, if you place an order online and choose the “Pay in Store” option, not only will the books be set aside for you, you’ll also see the exact total and will only have to take out what you need. This is a little trickier if you're shopping at a store without e-commerce, but, if you've got one of those fancy computers that also make phone calls in your pocket, you can calculate your cost. You spend the same amount, but the store makes more profit.

Take a Half Day During the Week: Things tend to be a little slower at stores in the mid-afternoon and mid-morning during the week. If you can arrange to shop during those times, not only will you have a relatively quiet, relatively stress-free shopping experience (and all the bookseller help you can stand if you're at PSB), you’ll lessen the rush on the weekends making it easier for other shoppers to shop. Spreading out the sales also makes it easier for employees to do the kind of maintenance (like re-shelving books and bringing down overstock) that make it easier for everyone to find what they're looking for. A store in good working order, with enough staff time to give the personalized service that makes shopping local such a pleasant experience, and a generally less Hunger Games atmosphere, all lead to more sales and more profits. (And just take a minute to dream with me here, and imagine your weekend, when you've done all the shopping on Wednesday.)

Bring Your Own Bag: Dude. Seriously. Are you still getting a bag whenever you go shopping? Sure, taking a bag isn't the most evil thing you can do, but it's probably the easiest evil thing to not do. Just put a collapsible bag in every single satchel, handbag, purse, carry-all, you've got (and maybe one in every coat). I mean, seriously, last I counted, we still only have one planet and last I checked, we're still punching it in the taint. Yes, there are a lot of things we're doing that are far worse (Hi there, mountain top coal mining and deep water oil drilling. Also, fuck you.) but these little daily habits add up when everybody does them all the time and they don't require a miracle of science to fix. At the store, I will give you a bag if you want one and I'll do it with a smile, because I don't know what is in your life that has brought you to this particular decision. I know there are times when a bag is totally justifiable and so when I'm behind the counter, in the moment, I always assume a customer takes a bag because it is one of those times. But, fuckin' seriously, dude, you have hands, you probably want Boston to not be underwater when your grandkids are adults, so fuckin' carry that shit out. Phew. OK. More to the point, bags are one of those little costs (like replacing all those pens that disappear) that chip away at profits. Most stores accept bags, pens, etc, as part of their operating costs, but that doesn't mean you need to use them. (Seriously, did you just “forget” I handed you that pen, like 3 seconds ago?) If you don't, the store makes more profits on the sale, the more profits they make, the more taxes they pay, the more inventory they buy, the more their employees make, the bigger the impact your dollar has on your community.

So to summarize: see you on Wednesday when you bring your own bag and pay in cash.

One more point to wrap this up. Shopping local is not a nostalgic pity party. It is not about preserving the good old days of ye olde maine ftreet fhop. This is rational self-interest. Yes, there is an emotional content to shopping locally (and given that humans are pretty emotional entities, it seems like that argument does belong in the whole “rational self-interest” thing but I don't want to make any economists cry right before the holidays) but there is also significant monetary value as well. Given all the data, even Ayn Rand would shop locally, except when she owned stock in national and international corporations. And that's really how you should think of shopping locally. (Swish.) You are simply buying from a company in which you own stock. The dividends aren't paid out the same way, but they are undeniable. And these three strategies will help increase your return on investment.

Pay in Cash: Credit cards are convenient, but that convenience comes at a cost. Some of it is interest payments and customer fees, but much of that cost is paid by the stores themselves in the form of merchant or vendor fees. (This is not a knock on it, but if you've ever wondered what's in it for American Express with the whole Small Business Saturday thing, this is it.) In the long term, these fees lead to more expensive stuff, as the fees are built into the cost of goods, and in the short term they can be a major burden on small businesses. After staffing, credit card processing fees tend to be the next biggest single non-discretionary expense. There are no fees for cash, of course. Cash, though, takes some planning ahead. At PSB at least, if you place an order online and choose the “Pay in Store” option, not only will the books be set aside for you, you’ll also see the exact total and will only have to take out what you need. This is a little trickier if you're shopping at a store without e-commerce, but, if you've got one of those fancy computers that also make phone calls in your pocket, you can calculate your cost. You spend the same amount, but the store makes more profit.

Take a Half Day During the Week: Things tend to be a little slower at stores in the mid-afternoon and mid-morning during the week. If you can arrange to shop during those times, not only will you have a relatively quiet, relatively stress-free shopping experience (and all the bookseller help you can stand if you're at PSB), you’ll lessen the rush on the weekends making it easier for other shoppers to shop. Spreading out the sales also makes it easier for employees to do the kind of maintenance (like re-shelving books and bringing down overstock) that make it easier for everyone to find what they're looking for. A store in good working order, with enough staff time to give the personalized service that makes shopping local such a pleasant experience, and a generally less Hunger Games atmosphere, all lead to more sales and more profits. (And just take a minute to dream with me here, and imagine your weekend, when you've done all the shopping on Wednesday.)

Bring Your Own Bag: Dude. Seriously. Are you still getting a bag whenever you go shopping? Sure, taking a bag isn't the most evil thing you can do, but it's probably the easiest evil thing to not do. Just put a collapsible bag in every single satchel, handbag, purse, carry-all, you've got (and maybe one in every coat). I mean, seriously, last I counted, we still only have one planet and last I checked, we're still punching it in the taint. Yes, there are a lot of things we're doing that are far worse (Hi there, mountain top coal mining and deep water oil drilling. Also, fuck you.) but these little daily habits add up when everybody does them all the time and they don't require a miracle of science to fix. At the store, I will give you a bag if you want one and I'll do it with a smile, because I don't know what is in your life that has brought you to this particular decision. I know there are times when a bag is totally justifiable and so when I'm behind the counter, in the moment, I always assume a customer takes a bag because it is one of those times. But, fuckin' seriously, dude, you have hands, you probably want Boston to not be underwater when your grandkids are adults, so fuckin' carry that shit out. Phew. OK. More to the point, bags are one of those little costs (like replacing all those pens that disappear) that chip away at profits. Most stores accept bags, pens, etc, as part of their operating costs, but that doesn't mean you need to use them. (Seriously, did you just “forget” I handed you that pen, like 3 seconds ago?) If you don't, the store makes more profits on the sale, the more profits they make, the more taxes they pay, the more inventory they buy, the more their employees make, the bigger the impact your dollar has on your community.

So to summarize: see you on Wednesday when you bring your own bag and pay in cash.

One more point to wrap this up. Shopping local is not a nostalgic pity party. It is not about preserving the good old days of ye olde maine ftreet fhop. This is rational self-interest. Yes, there is an emotional content to shopping locally (and given that humans are pretty emotional entities, it seems like that argument does belong in the whole “rational self-interest” thing but I don't want to make any economists cry right before the holidays) but there is also significant monetary value as well. Given all the data, even Ayn Rand would shop locally, except when she owned stock in national and international corporations. And that's really how you should think of shopping locally. (Swish.) You are simply buying from a company in which you own stock. The dividends aren't paid out the same way, but they are undeniable. And these three strategies will help increase your return on investment.

Wednesday, November 20, 2013

What Do We Use to Taste Our Food

I'm sure it will come as a shock to many of you that Riss and I started brewing our own beer about a year ago. (Well, Riss started brewing and I started occasionally helping her brew and occasionally being greeted when I got home from work on a Sunday with a statement like, “You like, kolsch, right?”) It has been a ton of fun and the beer has been fantastic. The most powerful taste experience I've had happened fairly early on when I drank one of our saisons. It was towards when I usually go to bed, I was a little peckish and decided to have a beer instead of a bowl of cereal. Beyond how great it tasted, drinking that saison felt physically good, as if it were biologically, bodily beneficial; as if the usually very abstract sense of health and nutrition materialized as an actual sensation of flavor. And, being me, rather than just enjoying it, I thought about it.

Beyond, perhaps an extra level of vitamin-B from the yeast, can we prove that home brew is, in fact, better than commercial beer? Could we chemically analyze the ingredients to determine if a certain kind of hops or malts or grains or yeasts produces different tastes when processed at different scales? Of course, as is natural, thinking about beer got me thinking about everything else. There is evidence that today's vegetables, for a whole host of reasons, have less nutritional content than vegetables from a generation or two ago, so does that explain why my farm share vegetables taste so good that store bought vegetables now taste like styrofoam that's punching me in the eye? Perhaps we simply underestimate the value of “freshness” with vegetables and the actual determining taste factor is the extra day between being picked and being eaten that all store bought veggies have. Maybe all those pesticides, no matter how thoroughly washed off, affect flavor.

The questions of taste and quality are, of course, compromised by all the various “brown bag” tests, that tend to show that, without the suggestion of the label, it is very difficult for most people to taste the difference between great wine and good wine, meaning the actual chemical difference, the actual physical interaction between the wine and your taste buds, what we actually taste is not meaningfully different; meaning that the bulk of what we taste, at least when we're tasting wine, is the idea of what the wine should taste like. If this is true for wine, is it true for organic farm share vegetables and home brewed beer?

Of course, advertisers have known for ages that the suggestion of a food experience is almost as important as the actual food in how the food is experienced. A McDonald's hamburger isn't really flavored with a cliff's worth of sodium and the mysterious greasy remains its brethren leave on the flat top; it's flavored by a gagillion dollar relentless advertising campaign abusing the cultural consciousness of the world into believing its food. The same goes for any food that is advertised, in any way. Food producers have discovered that it is more profitable to suggest their food tastes good, than to go through the trouble of trying to make sure their food is actually good.

One current in the interpretation of this phenomenon is to argue that there really isn't actual “quality” in terms of taste. For the most part, if you believe your are in a super classy restaurant that makes fantastic food, the majority of the classy fantastic-ness of your meal will come from you believing it will be classily fantastic and not from the food having any actual, provable class or fantasy. Of course, there is more to food than just taste, and too often this idea is used to apologize for destructive and unhealthy food practices. If we can't definitively, scientifically, empirically prove that say, a burger a Craigie on Main is better than a burger at McDonald's, than McDonald's is free to continue doing whatever it is they call “making a hamburger.”

Yes, it is important for food to taste good, but it is also important for food to not give us Type-2 diabetes, for our food system not to kill all the bees and help destroy the world, and for the way we prepare and eat our food to help us feel like actual fucking human beings and not just cogs in a vast capitalist system that need occasional refueling.

We taste with our brains. Our entire brains. We all know that food is flavored by our ideas of it and our memories of it—which is why there is such a thing as “comfort food”--but we can also taste with our politics, taste with our ethics, taste with our identities. If the vegetables I get from Steve also come with the knowledge they are not contributing to the destruction of civilization as we know it by pumping vast amounts of carbon into the atmosphere and thus changing the climate, while representing a scalable business model for a more just, more healthy, more community-based food system, why shouldn't they taste better to me than the vegetables that are part of a massive agri-business complex thriving through destructive and totally unsustainable monoculture? Even if chemically, even if the actual substances that hit my actual taste buds are not actually different, they are politically, economically, and socially different, so why shouldn't my primary sensory experience of them be radically different.

Though I doubt it, I suppose there is a chance that I cannot prove the beer that started this whole though is physically much different from a Bud Light (I mean, except for the whole one being a saison and the other being a pilsner, but I don't think there are any mainstream commercial saisons and that's not really the point anyway) but that beer and a Bud Light have different meaning in my life, so, of course I would experience them differently. In the end, we don't taste with our tongues, we taste with our lives.

Beyond, perhaps an extra level of vitamin-B from the yeast, can we prove that home brew is, in fact, better than commercial beer? Could we chemically analyze the ingredients to determine if a certain kind of hops or malts or grains or yeasts produces different tastes when processed at different scales? Of course, as is natural, thinking about beer got me thinking about everything else. There is evidence that today's vegetables, for a whole host of reasons, have less nutritional content than vegetables from a generation or two ago, so does that explain why my farm share vegetables taste so good that store bought vegetables now taste like styrofoam that's punching me in the eye? Perhaps we simply underestimate the value of “freshness” with vegetables and the actual determining taste factor is the extra day between being picked and being eaten that all store bought veggies have. Maybe all those pesticides, no matter how thoroughly washed off, affect flavor.

The questions of taste and quality are, of course, compromised by all the various “brown bag” tests, that tend to show that, without the suggestion of the label, it is very difficult for most people to taste the difference between great wine and good wine, meaning the actual chemical difference, the actual physical interaction between the wine and your taste buds, what we actually taste is not meaningfully different; meaning that the bulk of what we taste, at least when we're tasting wine, is the idea of what the wine should taste like. If this is true for wine, is it true for organic farm share vegetables and home brewed beer?

Of course, advertisers have known for ages that the suggestion of a food experience is almost as important as the actual food in how the food is experienced. A McDonald's hamburger isn't really flavored with a cliff's worth of sodium and the mysterious greasy remains its brethren leave on the flat top; it's flavored by a gagillion dollar relentless advertising campaign abusing the cultural consciousness of the world into believing its food. The same goes for any food that is advertised, in any way. Food producers have discovered that it is more profitable to suggest their food tastes good, than to go through the trouble of trying to make sure their food is actually good.

One current in the interpretation of this phenomenon is to argue that there really isn't actual “quality” in terms of taste. For the most part, if you believe your are in a super classy restaurant that makes fantastic food, the majority of the classy fantastic-ness of your meal will come from you believing it will be classily fantastic and not from the food having any actual, provable class or fantasy. Of course, there is more to food than just taste, and too often this idea is used to apologize for destructive and unhealthy food practices. If we can't definitively, scientifically, empirically prove that say, a burger a Craigie on Main is better than a burger at McDonald's, than McDonald's is free to continue doing whatever it is they call “making a hamburger.”

Yes, it is important for food to taste good, but it is also important for food to not give us Type-2 diabetes, for our food system not to kill all the bees and help destroy the world, and for the way we prepare and eat our food to help us feel like actual fucking human beings and not just cogs in a vast capitalist system that need occasional refueling.

We taste with our brains. Our entire brains. We all know that food is flavored by our ideas of it and our memories of it—which is why there is such a thing as “comfort food”--but we can also taste with our politics, taste with our ethics, taste with our identities. If the vegetables I get from Steve also come with the knowledge they are not contributing to the destruction of civilization as we know it by pumping vast amounts of carbon into the atmosphere and thus changing the climate, while representing a scalable business model for a more just, more healthy, more community-based food system, why shouldn't they taste better to me than the vegetables that are part of a massive agri-business complex thriving through destructive and totally unsustainable monoculture? Even if chemically, even if the actual substances that hit my actual taste buds are not actually different, they are politically, economically, and socially different, so why shouldn't my primary sensory experience of them be radically different.

Though I doubt it, I suppose there is a chance that I cannot prove the beer that started this whole though is physically much different from a Bud Light (I mean, except for the whole one being a saison and the other being a pilsner, but I don't think there are any mainstream commercial saisons and that's not really the point anyway) but that beer and a Bud Light have different meaning in my life, so, of course I would experience them differently. In the end, we don't taste with our tongues, we taste with our lives.

Wednesday, November 13, 2013

Review of Seiobo There Below

Seiobo There Below does not use expected grammar. Those look like sentences, but they are not. Those blocks of texts look like paragraphs but, with a few exceptions, they are not. Yes, there is every indication that this book is organized in chapters, but I do not believe those are chapters. We have to borrow from other modes of expression to describe the grammar of Seiobo. It could be organized into stanzas and lines. Or perhaps lines, scenes, and acts. Those are better, but still not quite accurate. Seiobo There Below is a symphony; it is written in instrument sections, movements, solos, fugues...and the impossibility of Seiobo is that it is designed to be experienced as you would listen to a symphony; hearing all of the different parts come together. Or maybe its a painting, with the “sentences,” “paragraphs,” and “chapters,” as canvas, color and brushstroke, and again, we are somehow supposed to “see” the totality even though we can only read it in its separate parts.

Seibo There Below opens with an image of a Kamo-hunter, a crane or heron like bird standing in the river, and the entire opening chapter, entitled “The Kamo-hunter,” is just that bird standing in that river while time exists within and around it. I believe this passage acts like the first 70 or so pages in In Search of Lost Time, setting up all of the ideas and themes of the symphony, both in its content (fair warning, there is a lot of nothing happening) and in its style. You'll know pretty quickly whether Seiobo is a book for you. For me I was enraptured immediately by the prose; “Everything around it moves, as if just this one time and one time only, as if the message of Heraclitus has arrived here though some deep current, from the distance of an entire universe, in spite of all the senseless obstacles, because the water moves, it flows, it arrives, and cascades;...” The rhythm. The precision. The obsessive doubling and tripling and quadrupling back over scenes and images to put every detail in its perfect place; or at least, put details in places where they draw the eye of the reader so as to create an opportunity for mystery; an Acropolis whose hill you can climb but whose place you can never reach and then you get hit by a car.

The obsessiveness of Laszlo's prose naturally finds itself drawn to express obsessive actions, which, also pretty naturally, sets much of the action in Japan where precision is an end in itself. We see the restoration of a sacred Buddha statue, the carving of a Noh mask (I highly recommend Kissing the Mask by William Vollman, a critical study on Noh theater and femininity which could almost be read as a companion piece to Seiobo), and the cyclical rebuilding of a Shinto shrine and the ritual of cutting down the trees used to build it. But we also see the preparation of a panel for an altar in Renaissance Europe (which is insane), the construction of a Renaissance dowry box, and the copying of a legendary Andrei Rublev icon, all with such an intensity of precision that you are left feeling as though you have learned everything you could ever learn about the topic, while understanding nothing about it. (Oh, and a homeless guy buys a sharp knife in Barcelona, because reasons.)

This tension between knowledge and understanding, between erudition and meaning, between precision and communication reinforces the tension between the temporal experience of physically reading the book and unified experience it strives for. The movement about rebuilding the shrine climaxes when a native of Kyoto who had been acting as a guide for a Western journalist friend, hikes the friend to the top of a small mountain with a panoramic view of Kyoto at night. The Western journalist concludes the exact opposite of what his Japanese guide intended. Another way to describe Seiobo There Below is a symphony in words in opposition to the opposition to that moment of opposition. (Yeah, I'm going to go with that.) Or perhaps it just is and is about the impossibility of perfection. Or something else perfectly unified and perfectly divided.

Like Everything Matters! which is one of the most sincerely optimistic books I've ever read that also happens to be about the apocalypse, Seiobo There Below is one of the most sincerely cynical books I've ever read that also happens to be about beauty. It is a beautifully written obsession with beauty that finds at the end of its obsession...something that is not beauty. An empty box. The mask for a monster. A painting never completed. A very sharp knife purchased by a man who cannot afford it. The one time you don't look both ways before crossing the street. The relentless hollowness of ever lasting life. A long-legged raptor in a river.

Seiobo There Below is one of those absolutely brilliant, absolutely beautiful, absolutely stunning books, I have a difficult time recommending at the bookstore. For reasons I can totally understand, a lot of people simply will not or don't want to deal with sentences this long or feel they require an actual story arc to get into a book, or have a details limit after which something better fucking happen or they are totally tapping out. It's not a book you can put in a stranger's hands. But it is a beautiful book. And, in some ways, it is the most thorough and most direct study of beauty I've ever read. And if you have wondered about the process and statement of beauty, Seiobo There Below is a hill you should climb whether the “Acropolis” on top is the “Acropolis” in your mind or not.

Seibo There Below opens with an image of a Kamo-hunter, a crane or heron like bird standing in the river, and the entire opening chapter, entitled “The Kamo-hunter,” is just that bird standing in that river while time exists within and around it. I believe this passage acts like the first 70 or so pages in In Search of Lost Time, setting up all of the ideas and themes of the symphony, both in its content (fair warning, there is a lot of nothing happening) and in its style. You'll know pretty quickly whether Seiobo is a book for you. For me I was enraptured immediately by the prose; “Everything around it moves, as if just this one time and one time only, as if the message of Heraclitus has arrived here though some deep current, from the distance of an entire universe, in spite of all the senseless obstacles, because the water moves, it flows, it arrives, and cascades;...” The rhythm. The precision. The obsessive doubling and tripling and quadrupling back over scenes and images to put every detail in its perfect place; or at least, put details in places where they draw the eye of the reader so as to create an opportunity for mystery; an Acropolis whose hill you can climb but whose place you can never reach and then you get hit by a car.

The obsessiveness of Laszlo's prose naturally finds itself drawn to express obsessive actions, which, also pretty naturally, sets much of the action in Japan where precision is an end in itself. We see the restoration of a sacred Buddha statue, the carving of a Noh mask (I highly recommend Kissing the Mask by William Vollman, a critical study on Noh theater and femininity which could almost be read as a companion piece to Seiobo), and the cyclical rebuilding of a Shinto shrine and the ritual of cutting down the trees used to build it. But we also see the preparation of a panel for an altar in Renaissance Europe (which is insane), the construction of a Renaissance dowry box, and the copying of a legendary Andrei Rublev icon, all with such an intensity of precision that you are left feeling as though you have learned everything you could ever learn about the topic, while understanding nothing about it. (Oh, and a homeless guy buys a sharp knife in Barcelona, because reasons.)

This tension between knowledge and understanding, between erudition and meaning, between precision and communication reinforces the tension between the temporal experience of physically reading the book and unified experience it strives for. The movement about rebuilding the shrine climaxes when a native of Kyoto who had been acting as a guide for a Western journalist friend, hikes the friend to the top of a small mountain with a panoramic view of Kyoto at night. The Western journalist concludes the exact opposite of what his Japanese guide intended. Another way to describe Seiobo There Below is a symphony in words in opposition to the opposition to that moment of opposition. (Yeah, I'm going to go with that.) Or perhaps it just is and is about the impossibility of perfection. Or something else perfectly unified and perfectly divided.

Like Everything Matters! which is one of the most sincerely optimistic books I've ever read that also happens to be about the apocalypse, Seiobo There Below is one of the most sincerely cynical books I've ever read that also happens to be about beauty. It is a beautifully written obsession with beauty that finds at the end of its obsession...something that is not beauty. An empty box. The mask for a monster. A painting never completed. A very sharp knife purchased by a man who cannot afford it. The one time you don't look both ways before crossing the street. The relentless hollowness of ever lasting life. A long-legged raptor in a river.

Seiobo There Below is one of those absolutely brilliant, absolutely beautiful, absolutely stunning books, I have a difficult time recommending at the bookstore. For reasons I can totally understand, a lot of people simply will not or don't want to deal with sentences this long or feel they require an actual story arc to get into a book, or have a details limit after which something better fucking happen or they are totally tapping out. It's not a book you can put in a stranger's hands. But it is a beautiful book. And, in some ways, it is the most thorough and most direct study of beauty I've ever read. And if you have wondered about the process and statement of beauty, Seiobo There Below is a hill you should climb whether the “Acropolis” on top is the “Acropolis” in your mind or not.

Tuesday, November 5, 2013

On Prizes

|

|

Are you sure, she's

never written about Gordie Howe?

|

But the question got me thinking about literature prizes in general, especially with the changes, considered and executed, to the National Book Award and the Man Booker Prize that generated so much controversy this fall. What should prizes do? What is the role of literature prizes in societ

|

|

I get it! It's a

metaphor for curling!

|

In general, I think it is more important for prizes to have clearly delineated goals, than for them to have any one goal in particular. I like the idea that there are prizes for particular kinds of books, written by authors with particular identities. I like that some prizes focus on individual works in a year and some prizes focus on the body of work over the course of a writing career. And I also like that there is a diversity in the selection process. I like that there is an Impact award that is open and there is a Nobel which is very closed. Which is not to say that prizes are perfect. Just like, well, everything, from time to time those responsible for administering them should reassess, should re-ask the big questions, should examine the process, and should make changes.

But even with my fairly flexible attitude towards prizes, I think there is one factor a prize should never, ever consider when determining its winner: popularity. There has been an increasing amount of chatter, especially about the National Book Award suggesting that, in order to more faithfully reflect the will of the reading public and to stay relevant to that reading public, prizes should consider a book's popularity when deciding on their award. That chatter is wrong. Overusing “literally” and “awesome” level wrong. Here are three reasons why.

Popularity has never, ever been an indicator of quality. Ultimately, prizes are about quality. Yes, quality is subjective and yes, determination of quality is influenced by the power structure of the times, and yes, personal biases, prejudices, and grudges can compromise selection, and yes, critics and judges can be completely out of touch with the culture over which they strive to preside, but quality still exists and, even though it lacks an absolute foundation, it is important for us to pursue it. A lot of different factors go in to determining whether a book is good or not, but perhaps the only factor we can definitively say does not indicate quality, one way or the other, is popularity. Many extremely popular books are also great works of literature. Many extremely popular books are an embarrassment to the alphabet. (Which does not mean I think people shouldn't buy and read them for entertainment. Also, this is not screed against popular books.) Many extremely popular books fall somewhere in between. The point is not that there is something wrong with popularity, but that it is not relevant in deciding which book in a particular category of books is the best. And this goes for rejecting a book because of its popularity; for assuming that simply because a lot of people bought it, it must be lowest-common-denominator product.

|

Finally, prizes are one of the great book discovery engines. They take authors known only to the literati and make them known to the public. They catch books that have slipped through the media cracks. They create a public discussion of a book that had not had a public discussion before. In some ways, this only really half a point, because it does argue that popularity can act as a disqualifier, but I have a slightly different take on it. As I mentioned above, one of the arguments for preferring popular books in an awards process is that it makes the book more relevant to the reading culture, but what is more relevant in culture; the leader or the follower? The coolest kid in high school is the one that starts the trend, not follows it. If prizes want to be “relevant” they need to be actors, not reactors, influencing new taste, rather than responding to existing taste. For example, Jennifer Egan's Pulitzer introduced the reading public to one of the most important American authors currently writing, and made a bestseller out of an innovative work at the edge of what might be next in fiction.

Judging quality in anything is a fraught and flawed process and too often, considerations outside quality determine the winner. But just because -isms can between between the award and the quality does not mean quality should no longer be the target. Sometimes the best book in whatever the prize looks to award is already extremely popular, sometimes it's not. Sometimes a prize will turn a book into a bestseller and sometimes it won't. Sometimes a prize will be the first step in the canonization of a work or an author and sometimes it will be a product of its time and reflect a fad or trend that will baffle future generations. Prizes have their problems, but they also have their purposes. And rewarding popularity shouldn't be one of them.

Wednesday, October 30, 2013

The Best Books from the Indies Introduce Debut Panel

There was a huge range in quality in what I read for the panel. A few books were agonizing to reach the required 50 pages. A few I plowed through hoping for a surprising or at least interesting ending that I didn't get. As I mentioned in my previous post, a few started out fantastic only to lose their way, and not in the post-modern Pynchonesque characters wandering in the void of existence way of losing their way. And a few were fucking fantastic. Here are the two best books, according to me, from the panel reading.

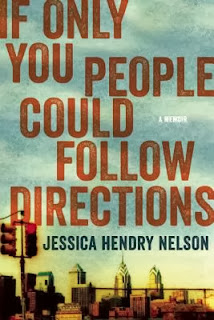

The Best Non-Fiction: If Only You People Could Follow Directions by Jessica Hendry Nelson (Coming out in January 2014)

My first thought when I started reading this book was: “Great, another addiction and dysfunction memoir, just what the world needs.” Though in many ways, Nelson's memoir is just that, she has made a narrative breakthrough that propelled her book to the top of the non-fiction heap. Rather than trying to jam the chaos of life into a chronological story-arc based narrative, Nelson explores her life through a series of essays that revolve around certain themes rather than certain times. Nelson bounces around in her life, she struggles with the ideas of her experiences and not just with the emotions of them, (though, also with the emotions of them) and through this has written a memoir that acts and feels like memory. Though the coping with addiction and dysfunction was compelling, the essay that convinced me of the depth of this book's value was “The Dollhouse,” in which she explores a very different kind of person.

Up till that essay, the book dealt with people we already knew from the genre of addiction and dysfunction memoir; the alcoholic father, the enabling mother, the brother following in the father's footsteps, and the troubled but charismatic best friend, but Cynthia, the focus of “The Dollhouse,” is an entirely different character. And though she is only the subject of one essay, she is as fully formed as any of the familiar characters in the book. That essay marks a thematic turning point in the book as afterward, Nelson explores more of her world outside of the dysfunctions she grew up with. We see her at a job in college, in New York, finding a partner, deciding to write, and finally, moving to Vermont where this collection was written and assembled. Which is not to say that everything in her life gets tied up in a neat little “struggle through strife to success package,” but that Nelson, despite how important the dysfunction was in her life can see and explore beyond it. Dysfunction is a part of her story, but not a part of her self.

There were a lot of typical ways Nelson could have presented the events in her life. The materials for the typical lurid memoir of drug, alcohol, and mental illness (probably) induced squalor are there. Instead, Nelson approached her life almost the way a critic would approach a work of literature; exploring the central themes, looking beyond the core characters, imagining other ways of being. Nelson has taken a genre that tends to be voyeur-bait and written a work of art. I hope more memoirists follow suit.

The Best Fiction: Faces in the Crowd by Valeria Luiselli (Coming out May 2014)

There are three narrative currents in Faces in the Crowd; the narrator living in Mexico City with her husband and children trying to write a novelization of poet Gilberto Owen's time in Harlem, the narrator remembering her time as a translator living in New York City that was the source of her idea for the novel, and the novel itself. Luiselli brilliantly weaves these currents together into a meditation on the nature of creation; not just creation of novels and poetry, but the creation of self and identity. The currents bleed into each other. Her husband reads over her shoulder. He leaves her or does not. Gilberto speaks in her prose. Translation hoax. Ghosts on the subway. The mix of fact and fiction both on the page and in the mind of the narrator.

One of the big weaknesses I saw in a number of the other books is the inability to differentiate character voices. Despite being different people, too often, different characters had the same narrative voice. In my own work, I've often found this process of differentiating voice the most difficult and time consuming part of the writing process. (see my earlier concerns about editing) In early drafts, all the characters sounded like me, in later drafts they all sounded like slightly different versions of me, rinse and repeat over the course of drafts (and years) until all of the characters had distinct, but not caricaturish, voices. So it is actually a fairly important demonstration of the bedrock quality of the work that the first-person voice of Gilberto Owen is very different from the first-person voice of the narrator describing her time in New York.

As a writer, I'm interested in how the author of a book earns my trust, how he or she proves to me the effort I'm going to put in to reading their book is going to be rewarded. For me, with Faces in the Crowd, it was the voice of the narrator's pre-school age son that earned my trust. Even more specifically, it was the word “workery,” the term the boy used to describe where his father went during the day, that showed me Luiselli was on to something. That one word demonstrates the character's playfulness, cleverness, and imagination and gives him an instant and recognizable voice. I dog-eared a dozen pages for brilliance. And in the end, we don't get a conclusion about the nature of poetry and identity, of authenticity and dishonesty, of art and self, but a moment of violent disruption that transfers the responsibility for further exploration from the narrator to the reader.

There were other good books in the pile for this panel, but these two blew the doors off everything else. Innovative. Sophisticated. Daring. Beautiful. I didn't know it at the beginning but If Only You People Could Follow Directions and Faces in the Crowd were exactly the kind of books I was hoping to discover this summer.

The Best Non-Fiction: If Only You People Could Follow Directions by Jessica Hendry Nelson (Coming out in January 2014)

My first thought when I started reading this book was: “Great, another addiction and dysfunction memoir, just what the world needs.” Though in many ways, Nelson's memoir is just that, she has made a narrative breakthrough that propelled her book to the top of the non-fiction heap. Rather than trying to jam the chaos of life into a chronological story-arc based narrative, Nelson explores her life through a series of essays that revolve around certain themes rather than certain times. Nelson bounces around in her life, she struggles with the ideas of her experiences and not just with the emotions of them, (though, also with the emotions of them) and through this has written a memoir that acts and feels like memory. Though the coping with addiction and dysfunction was compelling, the essay that convinced me of the depth of this book's value was “The Dollhouse,” in which she explores a very different kind of person.

Up till that essay, the book dealt with people we already knew from the genre of addiction and dysfunction memoir; the alcoholic father, the enabling mother, the brother following in the father's footsteps, and the troubled but charismatic best friend, but Cynthia, the focus of “The Dollhouse,” is an entirely different character. And though she is only the subject of one essay, she is as fully formed as any of the familiar characters in the book. That essay marks a thematic turning point in the book as afterward, Nelson explores more of her world outside of the dysfunctions she grew up with. We see her at a job in college, in New York, finding a partner, deciding to write, and finally, moving to Vermont where this collection was written and assembled. Which is not to say that everything in her life gets tied up in a neat little “struggle through strife to success package,” but that Nelson, despite how important the dysfunction was in her life can see and explore beyond it. Dysfunction is a part of her story, but not a part of her self.

There were a lot of typical ways Nelson could have presented the events in her life. The materials for the typical lurid memoir of drug, alcohol, and mental illness (probably) induced squalor are there. Instead, Nelson approached her life almost the way a critic would approach a work of literature; exploring the central themes, looking beyond the core characters, imagining other ways of being. Nelson has taken a genre that tends to be voyeur-bait and written a work of art. I hope more memoirists follow suit.

The Best Fiction: Faces in the Crowd by Valeria Luiselli (Coming out May 2014)

There are three narrative currents in Faces in the Crowd; the narrator living in Mexico City with her husband and children trying to write a novelization of poet Gilberto Owen's time in Harlem, the narrator remembering her time as a translator living in New York City that was the source of her idea for the novel, and the novel itself. Luiselli brilliantly weaves these currents together into a meditation on the nature of creation; not just creation of novels and poetry, but the creation of self and identity. The currents bleed into each other. Her husband reads over her shoulder. He leaves her or does not. Gilberto speaks in her prose. Translation hoax. Ghosts on the subway. The mix of fact and fiction both on the page and in the mind of the narrator.

One of the big weaknesses I saw in a number of the other books is the inability to differentiate character voices. Despite being different people, too often, different characters had the same narrative voice. In my own work, I've often found this process of differentiating voice the most difficult and time consuming part of the writing process. (see my earlier concerns about editing) In early drafts, all the characters sounded like me, in later drafts they all sounded like slightly different versions of me, rinse and repeat over the course of drafts (and years) until all of the characters had distinct, but not caricaturish, voices. So it is actually a fairly important demonstration of the bedrock quality of the work that the first-person voice of Gilberto Owen is very different from the first-person voice of the narrator describing her time in New York.

As a writer, I'm interested in how the author of a book earns my trust, how he or she proves to me the effort I'm going to put in to reading their book is going to be rewarded. For me, with Faces in the Crowd, it was the voice of the narrator's pre-school age son that earned my trust. Even more specifically, it was the word “workery,” the term the boy used to describe where his father went during the day, that showed me Luiselli was on to something. That one word demonstrates the character's playfulness, cleverness, and imagination and gives him an instant and recognizable voice. I dog-eared a dozen pages for brilliance. And in the end, we don't get a conclusion about the nature of poetry and identity, of authenticity and dishonesty, of art and self, but a moment of violent disruption that transfers the responsibility for further exploration from the narrator to the reader.

There were other good books in the pile for this panel, but these two blew the doors off everything else. Innovative. Sophisticated. Daring. Beautiful. I didn't know it at the beginning but If Only You People Could Follow Directions and Faces in the Crowd were exactly the kind of books I was hoping to discover this summer.

Wednesday, October 23, 2013

Something About the Reaping

|

| What did we sew?! |

What I am about to say should not be construed as in any way suggesting for a second, that there was a shred of rationale behind the shut down. But, we should have seen this nonsense coming a mile away.

Remember how the Tea Party came to its level of power in American politics. The 2010 election happened after a coordinated two-year campaign of misinformation and outright lies about the content of the President's character and the nature of his policies. The public was told he was not a U.S. citizen, that he was a secret Muslim, that he was coming for your guns and your bibles. They were told he hated America, that he hated freedom, that he wanted to turn us into Europe. They were told to fear sharia law. They were told he was waging a war on Christianity, on the heteronormative family, on, I don't know, apple pie and chicken and waffles. It was a fairly mainstream smear campaign against the sitting President of the United States of America and the spear point of this attack was Obamacare.

While the President and Congressional Democrats were busy crafting an extremely complex, fairly conservative overhaul of a health care system in which you could go bankrupt from getting cancer, Republicans and Fox News were busy telling the public Obamacare was a ploy to kill your grandparents and fill your daughters with birth control. Republicans saw the somewhat reasonable public confusion around Obamacare, and rather than, I don't know, engaging in a rational debate about the shortcomings of market based health care or the specifics of the legislation itself, spent their time shouting that Obamacare was socialism, that it was the end of freedom, that it was tyranny, that it represented the death of the United States of America.

Republicans saw an electoral opportunity; a chance to de-legitimize one of the most popular campaign platforms in recent memory and they took it. They threw the equivalent of a tantrum in the legislature. They flat out lied to the media. The media, for the most part, did not refute the lies, and, leveraging the unease the country still felt about the economy, the still fairly verdant forest of racism, and the standard issue persecution complex of conservative Christians, Republicans orchestrated a historic power shift in the House of Representatives and in state legislatures. The Tea Party was not, strictly, a Republican creation, but Republicans were more than happy to use them as a way to return to a fair amount of legislative power.

As a pretty obvious consequence, about 30 people were elected who actually believe Obamacare represents the end of America. To pose a somewhat delicate question: what the fuck did mainstream Republicans think was going to happen? They spent two years telling the country Obama was the devil. Obviously, they would end up with a few elected officials with little Rs next to their names who believe that Obama is the devil.

The shut down and threatened default were pretty natural consequences of the 2010 Republican campaign strategy. We all have reaped, what they sowed.

The interesting question now is, what happens in a couple months when the funding runs out again and the debt ceiling looms again? I'm sure the Tea Party members in the house are willing to shut down the government and risk default again, especially if Democrats try to act like Democrats in the coming budget negotiations (which the Senate has been asking for) but are more moderate mainstream Republicans? And if they're not, how are they going to ensure their party doesn't look ridiculous again? Are they willing to risk losing seats to disavow the policies and tactics of the Tea Party? And exactly how much are Democrats willing to help Boehner and the mainstream Republicans save face, especially given the total dick press release Boehner put out about the compromise spending bill? (And, you know, the five plus years of general legislative dickishness.)

Perhaps the greatest tragedy of this entire debacle, is how it probably won't matter all that much in the 2014 elections. Since our media is utterly incapable of providing historic context for the issues at hand, the election will most likely be decided by A. A major change in the employment rate one way or the other in October B. a major change in the cost of healthcare one way or the other in October, or C. Some weird October shit that isn't particularly relevant to the issues at hand, but still has emotional relevance. For a moment though, the vast majority of the country saw the Tea Party Republicans for what they are; shortsighted, dogmatic, ideologues with no ability to see beyond their one or two primary goals. Let's just hope we can remember that in November 2014.

All political systems have flaws. No matter how well planned, how inherently stable, how just a system might be, situations can arise that put stress on the seams of the system. There are a lot of flaws in the current two-party incarnation of American politics, but, for the most part, until now the stress has not been felt by the system itself, but by the less powerful (i.e. just about everybody) with varying degrees of tolerability. But the Republican Party, since they pledged to make Obama a one-term president and reaching a kind of crescendo with the most recent shut down are putting stress on the seams of our manner of government. For the most part it has been in the Senate through filibusters and anonymous holds, but now they've shown that, limiting choice to A and B, allows A and/or B immense of amounts of power, regardless of how many voters they actually represent. Perhaps the biggest mistake the Democrats, Harry Reid and Barack Obama in particular, is to continue to believe in the strength of the political system. Over the last five years, both of them (though Reid more definitively) have had opportunities to use different legislative and negotiating techniques, but because they believe the system itself is so strong, five years after one of the most decisive Democrat swings in recent memory, and one year after a public repudiation of many of the key planks of the Republican platform we have an austerity Republican government that can't even effectively legislate for the benefit of the 1% they so often shill for.

Thursday, October 17, 2013

The Indies Introduce Panel Debrief

As I blogged about earlier, this summer I participated in a panel that selected 10 debut books coming out in the Spring of 2014 for special promotions. From about the middle of July to the beginning of September I read from cover to shining cover 14 books and at least 50 pages (sometimes much more) of 17 more. Here is the good, the bad, and the interesting of that reading experience.

The Good

Your favorite author was once a debut author. Everyone's favorite author was once a debut author. But debut authors are a big risk for publishers. There are so many unknowns that go into signing and publishing an author for the first time and every one of those unknowns is a potential monetary loss. There's a chance said author will receive good review coverage, but there's a better chance the limited (in some ways) review coverage will go to an author the reviewer does not need to spend text introducing to the public. There's a chance a solid author tour will garner attention, that galleys of the book will get in the right hands and those hands will actually open said galleys so the eyes can eat the words, that the word of mouth support will be enough to at least see the bottom line and to establish some presence in the minds of the book buying public so the next book will get much more exposure, but it is more likely few people will go to debut author events, the galleys won't get opened, and the book won't sell enough to recoup the investment. But every great, guaranteed best-seller was once a debut, so publishers continue to take the risk.

But with publishing margins slimmed by a whole host of different economic and social forces, it wouldn't be that surprising to see publishers taking fewer risks and publishing fewer debut authors. You wonder if publishers will be willing to endure the sales of, for example, Ann Patchett's first book, no matter how much they believe in the talent of the author. (Fewer books being published in the traditional way would probably be a good thing, but not for this reason and that's a different post anyway.(And, of course, they're still one book short.)) This panel shows that not only are publishers committed to publishing debut authors (each publisher could only submit three titles), but they are finding cost-effective ways to support those debut authors. With so much of our book economy making so much of traditional publishing more difficult, (i.e. as the necessary capital is squeezed out of publishing by lower margins and lower sales) it is exciting to see publishers taking steps to make sure they continue what may be their most bottom-line damaging responsibility.

The Bad

So those bottom lines? Man, keeping those lights on and shit, huh? As publishers struggle, one of the concerns in the readerly world, is that they will skimp on editing; not proofreading, but that process by which a work of potential genius is improved, idea by idea, character by character, chapter by chapter, sentence by sentence, word by word into a work of actual genius; that weird alchemical art that discerns the potential of a work of literature and then induces the writer to reach that potential; the long, labor intensive, and thus, in many ways, expensive process, that can be a vital part of producing great works of human culture. That editing. And given that there is absolutely no correlation between quality and sales, one could not blame a publisher, or at least an accountant who works for a publisher, for asking whether it is really worth the cost to make a good work great.

But it is almost impossible to figure out whether capital restrictions are lessening the quality of published books. There just isn't a way to create any kind of meaningful data about un-reached potential. However, an alarming number of books I read for this panel, including a few I really liked, had very strong beginnings, and a marked tapering off in quality by the end. To put this another way; the chapters that would land an agent, and the chapters that an agent would use to get a contract, and the chapters likely to earn a purchase at the bookstore, were excellent while the rest tended to be mediocre. And what I saw were not issues of copy editing or proofreading (which are forgiven in galleys), but fundamental questions on the direction of the stories and the development (or not) of the characters and themes. In short, a solid number of the submitted books seemed to suffer from a lack of editing, the important editing that makes a good work great.

As I said, this doesn't really mean there is a trend of diminishing editing in publishing. Maybe the time and money was spent and what was produced really had reached its potential. Maybe the particular editors themselves weren't great editors. Maybe great advice was not taken. Maybe each book in which I saw this issue has its own perfectly rational explanation and this concern is totally unfounded. Still, a pattern is a pattern and it was a troubling pattern.

The Interesting

We needed to chose 10 books and we had slimmed the list to 11. One of them had to go. Our system worked out that the 10th would be occupied by one of two books. I actively supported one and really disparaged the other, another reader actively supported what I disparaged and disparaged what I actively supported. What's interesting is that, despite being very different books, we each made the exact same case for our opinions. I thought one of the books was totally derivative and, though competently executed, wholly devoid of anything new, original, or even interesting to say about the human condition. My compatriot thought the same thing about the book I liked. Despite being very different in terms of content and style, sometimes our exchanges were more like echoes than debates. Books are powerful because the exact same words create different reactions in different readers. One of the currents of the vibrancy of reading comes from the fact that people can have different opinions about the same book. Everyone knows that, so that's not interesting. But this was a scale, or type, or flavor of differing opinion that I hadn't encountered before. What this tells me is that two avid readers, reading in the same language and same culture, even sharing some opinions and reading priorities, can still live on, essentially separate reading planets. That speaks to the diversity of literature of course, but also the diversity of quality in literature.

Next in interesting, we've all had to read books we don't like in school and we all know how miserable that can be. I also had to read (all the way to the end) some books I didn't like, but it was a very different experience. Because I volunteered for this panel and because I felt a responsibility to the other panelists and because I felt a responsibility to the authors, the misery of slogging through an awful book in order to turn in a half-assed book report so your parents don't get mad at you for a bad grade, was not present. There really were times when a good old fashioned read-it-while-blacked-out was pretty appealing. But that school room angst wasn't there. The pressure to do this reading came only from myself and so it was easier to transition my reading experience from debilitating agony to the observation of my debilitating agony in an attempt to extract something useful about life, the universe, and everything from these awful, awful books.

The Big Wrap Up

Given the length of this post, I'll post about my two favorite books later (I believe this is what they call in the business a “teaser.”), but it seems like I should come to some conclusions. Here they are in list form.

All told it was fun and challenging book binge, the piled remnants of which I still have no idea what to do with. What did you do on your summer vacation?

|

| The Finished |

Your favorite author was once a debut author. Everyone's favorite author was once a debut author. But debut authors are a big risk for publishers. There are so many unknowns that go into signing and publishing an author for the first time and every one of those unknowns is a potential monetary loss. There's a chance said author will receive good review coverage, but there's a better chance the limited (in some ways) review coverage will go to an author the reviewer does not need to spend text introducing to the public. There's a chance a solid author tour will garner attention, that galleys of the book will get in the right hands and those hands will actually open said galleys so the eyes can eat the words, that the word of mouth support will be enough to at least see the bottom line and to establish some presence in the minds of the book buying public so the next book will get much more exposure, but it is more likely few people will go to debut author events, the galleys won't get opened, and the book won't sell enough to recoup the investment. But every great, guaranteed best-seller was once a debut, so publishers continue to take the risk.

But with publishing margins slimmed by a whole host of different economic and social forces, it wouldn't be that surprising to see publishers taking fewer risks and publishing fewer debut authors. You wonder if publishers will be willing to endure the sales of, for example, Ann Patchett's first book, no matter how much they believe in the talent of the author. (Fewer books being published in the traditional way would probably be a good thing, but not for this reason and that's a different post anyway.(And, of course, they're still one book short.)) This panel shows that not only are publishers committed to publishing debut authors (each publisher could only submit three titles), but they are finding cost-effective ways to support those debut authors. With so much of our book economy making so much of traditional publishing more difficult, (i.e. as the necessary capital is squeezed out of publishing by lower margins and lower sales) it is exciting to see publishers taking steps to make sure they continue what may be their most bottom-line damaging responsibility.

The Bad

|

| The Read-a-Bunch-Of |

So those bottom lines? Man, keeping those lights on and shit, huh? As publishers struggle, one of the concerns in the readerly world, is that they will skimp on editing; not proofreading, but that process by which a work of potential genius is improved, idea by idea, character by character, chapter by chapter, sentence by sentence, word by word into a work of actual genius; that weird alchemical art that discerns the potential of a work of literature and then induces the writer to reach that potential; the long, labor intensive, and thus, in many ways, expensive process, that can be a vital part of producing great works of human culture. That editing. And given that there is absolutely no correlation between quality and sales, one could not blame a publisher, or at least an accountant who works for a publisher, for asking whether it is really worth the cost to make a good work great.

But it is almost impossible to figure out whether capital restrictions are lessening the quality of published books. There just isn't a way to create any kind of meaningful data about un-reached potential. However, an alarming number of books I read for this panel, including a few I really liked, had very strong beginnings, and a marked tapering off in quality by the end. To put this another way; the chapters that would land an agent, and the chapters that an agent would use to get a contract, and the chapters likely to earn a purchase at the bookstore, were excellent while the rest tended to be mediocre. And what I saw were not issues of copy editing or proofreading (which are forgiven in galleys), but fundamental questions on the direction of the stories and the development (or not) of the characters and themes. In short, a solid number of the submitted books seemed to suffer from a lack of editing, the important editing that makes a good work great.

As I said, this doesn't really mean there is a trend of diminishing editing in publishing. Maybe the time and money was spent and what was produced really had reached its potential. Maybe the particular editors themselves weren't great editors. Maybe great advice was not taken. Maybe each book in which I saw this issue has its own perfectly rational explanation and this concern is totally unfounded. Still, a pattern is a pattern and it was a troubling pattern.

The Interesting

|

| The Cat (Unreadable) |

Next in interesting, we've all had to read books we don't like in school and we all know how miserable that can be. I also had to read (all the way to the end) some books I didn't like, but it was a very different experience. Because I volunteered for this panel and because I felt a responsibility to the other panelists and because I felt a responsibility to the authors, the misery of slogging through an awful book in order to turn in a half-assed book report so your parents don't get mad at you for a bad grade, was not present. There really were times when a good old fashioned read-it-while-blacked-out was pretty appealing. But that school room angst wasn't there. The pressure to do this reading came only from myself and so it was easier to transition my reading experience from debilitating agony to the observation of my debilitating agony in an attempt to extract something useful about life, the universe, and everything from these awful, awful books.

The Big Wrap Up

Given the length of this post, I'll post about my two favorite books later (I believe this is what they call in the business a “teaser.”), but it seems like I should come to some conclusions. Here they are in list form.

I would totally read for a prize/panel again.

Being forced to read what you would not normally read every now and then is a very good thing.

Indie booksellers have, perhaps, the ideal mix of passion and reasonableness. Seriously, there were exchanges that went something like “I will cut myself in visible places if this book is not included in the top ten, but I've got to get back on the floor so if everybody else is OK with cutting it, I'm cool with cutting it.” How about we govern for a bit?

New art is still being written...

but much more new entertainment is still being written...

which is fine...

though I'd really like to see a little more art.

All told it was fun and challenging book binge, the piled remnants of which I still have no idea what to do with. What did you do on your summer vacation?

Wednesday, September 25, 2013

Questions About Reading

A friend of mine, who is a teacher, asked me if she could teach my post How You Find Books, How Books Find You, in the context of choosing independent reading. That is bucket-list awesome. What is even awesomer is her students asked some very thoughtful questions, the kind of simple, direct, but also really important and challenging questions, young people are uniquely capable of asking, and because I am a responsible adult, I answered them as best as I could. So here are their questions and my answers. Fair warning, I list a little towards the shmaltzy at times, but, hey, I'm talking about reading to kids. That's gonna happen.

What made you pick up The Haunted Bookshop instead of you other choices?

As a bookseller I've developed a really close relationship with the publisher, so I know there's a good chance I'm going to like anything they send me. They told me this book was a great celebration of bookselling and given that I was at the end of a very exhausting bookselling project I was looking for a "remind me why I do this," kind of experience. FYI, I started reading Seiobo There Below and it also would have been the perfect book. Its long, lyrical, and artistic sentences, the complexity of the images, the fact that its chapters are number with a Fibonnacci Sequence (1, 2, [1+2] 3, [3+2] 5...), the hyperfocus, the flat-out gutsyness (I'd probably prefer to say "ballsiness" but feel free to use "gutsyness") of attempting a book like this, are all things I love about books and were pretty much completely absent from the books I read for the panel.)

What strategies do you use to identify if you will enjoy a book? How do you know before you start reading it/how do you essentially choose your book?

Sometimes I listen to suggestions. There are some authors whose books I will always read. Sometimes I'm intrigued by the plot. Sometimes I happen to start reading and am intrigued by the style. The important thing is that I listen to my own brain when I'm interacting with a book. Do I feel interested? Do I feel as though my mental ears have perked up? Do I want to know more about whatever the book is saying? If yes, I'll read the book. But if I don't "hear" my brain doing those things, I probably don't read the book.

What genre of book is your favorite? I love mysteries.