There was a huge range in quality in what I read for the panel. A few books were agonizing to reach the required 50 pages. A few I plowed through hoping for a surprising or at least interesting ending that I didn't get. As I mentioned in my previous post, a few started out fantastic only to lose their way, and not in the post-modern Pynchonesque characters wandering in the void of existence way of losing their way. And a few were fucking fantastic. Here are the two best books, according to me, from the panel reading.

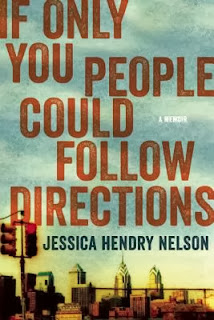

The Best Non-Fiction: If Only You People Could Follow Directions by Jessica Hendry Nelson (Coming out in January 2014)

My first thought when I started reading this book was: “Great, another addiction and dysfunction memoir, just what the world needs.” Though in many ways, Nelson's memoir is just that, she has made a narrative breakthrough that propelled her book to the top of the non-fiction heap. Rather than trying to jam the chaos of life into a chronological story-arc based narrative, Nelson explores her life through a series of essays that revolve around certain themes rather than certain times. Nelson bounces around in her life, she struggles with the ideas of her experiences and not just with the emotions of them, (though, also with the emotions of them) and through this has written a memoir that acts and feels like memory. Though the coping with addiction and dysfunction was compelling, the essay that convinced me of the depth of this book's value was “The Dollhouse,” in which she explores a very different kind of person.

Up till that essay, the book dealt with people we already knew from the genre of addiction and dysfunction memoir; the alcoholic father, the enabling mother, the brother following in the father's footsteps, and the troubled but charismatic best friend, but Cynthia, the focus of “The Dollhouse,” is an entirely different character. And though she is only the subject of one essay, she is as fully formed as any of the familiar characters in the book. That essay marks a thematic turning point in the book as afterward, Nelson explores more of her world outside of the dysfunctions she grew up with. We see her at a job in college, in New York, finding a partner, deciding to write, and finally, moving to Vermont where this collection was written and assembled. Which is not to say that everything in her life gets tied up in a neat little “struggle through strife to success package,” but that Nelson, despite how important the dysfunction was in her life can see and explore beyond it. Dysfunction is a part of her story, but not a part of her self.

There were a lot of typical ways Nelson could have presented the events in her life. The materials for the typical lurid memoir of drug, alcohol, and mental illness (probably) induced squalor are there. Instead, Nelson approached her life almost the way a critic would approach a work of literature; exploring the central themes, looking beyond the core characters, imagining other ways of being. Nelson has taken a genre that tends to be voyeur-bait and written a work of art. I hope more memoirists follow suit.

The Best Fiction: Faces in the Crowd by Valeria Luiselli (Coming out May 2014)

There are three narrative currents in Faces in the Crowd; the narrator living in Mexico City with her husband and children trying to write a novelization of poet Gilberto Owen's time in Harlem, the narrator remembering her time as a translator living in New York City that was the source of her idea for the novel, and the novel itself. Luiselli brilliantly weaves these currents together into a meditation on the nature of creation; not just creation of novels and poetry, but the creation of self and identity. The currents bleed into each other. Her husband reads over her shoulder. He leaves her or does not. Gilberto speaks in her prose. Translation hoax. Ghosts on the subway. The mix of fact and fiction both on the page and in the mind of the narrator.

One of the big weaknesses I saw in a number of the other books is the inability to differentiate character voices. Despite being different people, too often, different characters had the same narrative voice. In my own work, I've often found this process of differentiating voice the most difficult and time consuming part of the writing process. (see my earlier concerns about editing) In early drafts, all the characters sounded like me, in later drafts they all sounded like slightly different versions of me, rinse and repeat over the course of drafts (and years) until all of the characters had distinct, but not caricaturish, voices. So it is actually a fairly important demonstration of the bedrock quality of the work that the first-person voice of Gilberto Owen is very different from the first-person voice of the narrator describing her time in New York.

As a writer, I'm interested in how the author of a book earns my trust, how he or she proves to me the effort I'm going to put in to reading their book is going to be rewarded. For me, with Faces in the Crowd, it was the voice of the narrator's pre-school age son that earned my trust. Even more specifically, it was the word “workery,” the term the boy used to describe where his father went during the day, that showed me Luiselli was on to something. That one word demonstrates the character's playfulness, cleverness, and imagination and gives him an instant and recognizable voice. I dog-eared a dozen pages for brilliance. And in the end, we don't get a conclusion about the nature of poetry and identity, of authenticity and dishonesty, of art and self, but a moment of violent disruption that transfers the responsibility for further exploration from the narrator to the reader.

There were other good books in the pile for this panel, but these two blew the doors off everything else. Innovative. Sophisticated. Daring. Beautiful. I didn't know it at the beginning but If Only You People Could Follow Directions and Faces in the Crowd were exactly the kind of books I was hoping to discover this summer.

Wednesday, October 30, 2013

Wednesday, October 23, 2013

Something About the Reaping

|

| What did we sew?! |

What I am about to say should not be construed as in any way suggesting for a second, that there was a shred of rationale behind the shut down. But, we should have seen this nonsense coming a mile away.

Remember how the Tea Party came to its level of power in American politics. The 2010 election happened after a coordinated two-year campaign of misinformation and outright lies about the content of the President's character and the nature of his policies. The public was told he was not a U.S. citizen, that he was a secret Muslim, that he was coming for your guns and your bibles. They were told he hated America, that he hated freedom, that he wanted to turn us into Europe. They were told to fear sharia law. They were told he was waging a war on Christianity, on the heteronormative family, on, I don't know, apple pie and chicken and waffles. It was a fairly mainstream smear campaign against the sitting President of the United States of America and the spear point of this attack was Obamacare.

While the President and Congressional Democrats were busy crafting an extremely complex, fairly conservative overhaul of a health care system in which you could go bankrupt from getting cancer, Republicans and Fox News were busy telling the public Obamacare was a ploy to kill your grandparents and fill your daughters with birth control. Republicans saw the somewhat reasonable public confusion around Obamacare, and rather than, I don't know, engaging in a rational debate about the shortcomings of market based health care or the specifics of the legislation itself, spent their time shouting that Obamacare was socialism, that it was the end of freedom, that it was tyranny, that it represented the death of the United States of America.

Republicans saw an electoral opportunity; a chance to de-legitimize one of the most popular campaign platforms in recent memory and they took it. They threw the equivalent of a tantrum in the legislature. They flat out lied to the media. The media, for the most part, did not refute the lies, and, leveraging the unease the country still felt about the economy, the still fairly verdant forest of racism, and the standard issue persecution complex of conservative Christians, Republicans orchestrated a historic power shift in the House of Representatives and in state legislatures. The Tea Party was not, strictly, a Republican creation, but Republicans were more than happy to use them as a way to return to a fair amount of legislative power.

As a pretty obvious consequence, about 30 people were elected who actually believe Obamacare represents the end of America. To pose a somewhat delicate question: what the fuck did mainstream Republicans think was going to happen? They spent two years telling the country Obama was the devil. Obviously, they would end up with a few elected officials with little Rs next to their names who believe that Obama is the devil.

The shut down and threatened default were pretty natural consequences of the 2010 Republican campaign strategy. We all have reaped, what they sowed.

The interesting question now is, what happens in a couple months when the funding runs out again and the debt ceiling looms again? I'm sure the Tea Party members in the house are willing to shut down the government and risk default again, especially if Democrats try to act like Democrats in the coming budget negotiations (which the Senate has been asking for) but are more moderate mainstream Republicans? And if they're not, how are they going to ensure their party doesn't look ridiculous again? Are they willing to risk losing seats to disavow the policies and tactics of the Tea Party? And exactly how much are Democrats willing to help Boehner and the mainstream Republicans save face, especially given the total dick press release Boehner put out about the compromise spending bill? (And, you know, the five plus years of general legislative dickishness.)

Perhaps the greatest tragedy of this entire debacle, is how it probably won't matter all that much in the 2014 elections. Since our media is utterly incapable of providing historic context for the issues at hand, the election will most likely be decided by A. A major change in the employment rate one way or the other in October B. a major change in the cost of healthcare one way or the other in October, or C. Some weird October shit that isn't particularly relevant to the issues at hand, but still has emotional relevance. For a moment though, the vast majority of the country saw the Tea Party Republicans for what they are; shortsighted, dogmatic, ideologues with no ability to see beyond their one or two primary goals. Let's just hope we can remember that in November 2014.

All political systems have flaws. No matter how well planned, how inherently stable, how just a system might be, situations can arise that put stress on the seams of the system. There are a lot of flaws in the current two-party incarnation of American politics, but, for the most part, until now the stress has not been felt by the system itself, but by the less powerful (i.e. just about everybody) with varying degrees of tolerability. But the Republican Party, since they pledged to make Obama a one-term president and reaching a kind of crescendo with the most recent shut down are putting stress on the seams of our manner of government. For the most part it has been in the Senate through filibusters and anonymous holds, but now they've shown that, limiting choice to A and B, allows A and/or B immense of amounts of power, regardless of how many voters they actually represent. Perhaps the biggest mistake the Democrats, Harry Reid and Barack Obama in particular, is to continue to believe in the strength of the political system. Over the last five years, both of them (though Reid more definitively) have had opportunities to use different legislative and negotiating techniques, but because they believe the system itself is so strong, five years after one of the most decisive Democrat swings in recent memory, and one year after a public repudiation of many of the key planks of the Republican platform we have an austerity Republican government that can't even effectively legislate for the benefit of the 1% they so often shill for.

Thursday, October 17, 2013

The Indies Introduce Panel Debrief

As I blogged about earlier, this summer I participated in a panel that selected 10 debut books coming out in the Spring of 2014 for special promotions. From about the middle of July to the beginning of September I read from cover to shining cover 14 books and at least 50 pages (sometimes much more) of 17 more. Here is the good, the bad, and the interesting of that reading experience.

The Good

Your favorite author was once a debut author. Everyone's favorite author was once a debut author. But debut authors are a big risk for publishers. There are so many unknowns that go into signing and publishing an author for the first time and every one of those unknowns is a potential monetary loss. There's a chance said author will receive good review coverage, but there's a better chance the limited (in some ways) review coverage will go to an author the reviewer does not need to spend text introducing to the public. There's a chance a solid author tour will garner attention, that galleys of the book will get in the right hands and those hands will actually open said galleys so the eyes can eat the words, that the word of mouth support will be enough to at least see the bottom line and to establish some presence in the minds of the book buying public so the next book will get much more exposure, but it is more likely few people will go to debut author events, the galleys won't get opened, and the book won't sell enough to recoup the investment. But every great, guaranteed best-seller was once a debut, so publishers continue to take the risk.

But with publishing margins slimmed by a whole host of different economic and social forces, it wouldn't be that surprising to see publishers taking fewer risks and publishing fewer debut authors. You wonder if publishers will be willing to endure the sales of, for example, Ann Patchett's first book, no matter how much they believe in the talent of the author. (Fewer books being published in the traditional way would probably be a good thing, but not for this reason and that's a different post anyway.(And, of course, they're still one book short.)) This panel shows that not only are publishers committed to publishing debut authors (each publisher could only submit three titles), but they are finding cost-effective ways to support those debut authors. With so much of our book economy making so much of traditional publishing more difficult, (i.e. as the necessary capital is squeezed out of publishing by lower margins and lower sales) it is exciting to see publishers taking steps to make sure they continue what may be their most bottom-line damaging responsibility.

The Bad

So those bottom lines? Man, keeping those lights on and shit, huh? As publishers struggle, one of the concerns in the readerly world, is that they will skimp on editing; not proofreading, but that process by which a work of potential genius is improved, idea by idea, character by character, chapter by chapter, sentence by sentence, word by word into a work of actual genius; that weird alchemical art that discerns the potential of a work of literature and then induces the writer to reach that potential; the long, labor intensive, and thus, in many ways, expensive process, that can be a vital part of producing great works of human culture. That editing. And given that there is absolutely no correlation between quality and sales, one could not blame a publisher, or at least an accountant who works for a publisher, for asking whether it is really worth the cost to make a good work great.

But it is almost impossible to figure out whether capital restrictions are lessening the quality of published books. There just isn't a way to create any kind of meaningful data about un-reached potential. However, an alarming number of books I read for this panel, including a few I really liked, had very strong beginnings, and a marked tapering off in quality by the end. To put this another way; the chapters that would land an agent, and the chapters that an agent would use to get a contract, and the chapters likely to earn a purchase at the bookstore, were excellent while the rest tended to be mediocre. And what I saw were not issues of copy editing or proofreading (which are forgiven in galleys), but fundamental questions on the direction of the stories and the development (or not) of the characters and themes. In short, a solid number of the submitted books seemed to suffer from a lack of editing, the important editing that makes a good work great.

As I said, this doesn't really mean there is a trend of diminishing editing in publishing. Maybe the time and money was spent and what was produced really had reached its potential. Maybe the particular editors themselves weren't great editors. Maybe great advice was not taken. Maybe each book in which I saw this issue has its own perfectly rational explanation and this concern is totally unfounded. Still, a pattern is a pattern and it was a troubling pattern.

The Interesting

We needed to chose 10 books and we had slimmed the list to 11. One of them had to go. Our system worked out that the 10th would be occupied by one of two books. I actively supported one and really disparaged the other, another reader actively supported what I disparaged and disparaged what I actively supported. What's interesting is that, despite being very different books, we each made the exact same case for our opinions. I thought one of the books was totally derivative and, though competently executed, wholly devoid of anything new, original, or even interesting to say about the human condition. My compatriot thought the same thing about the book I liked. Despite being very different in terms of content and style, sometimes our exchanges were more like echoes than debates. Books are powerful because the exact same words create different reactions in different readers. One of the currents of the vibrancy of reading comes from the fact that people can have different opinions about the same book. Everyone knows that, so that's not interesting. But this was a scale, or type, or flavor of differing opinion that I hadn't encountered before. What this tells me is that two avid readers, reading in the same language and same culture, even sharing some opinions and reading priorities, can still live on, essentially separate reading planets. That speaks to the diversity of literature of course, but also the diversity of quality in literature.

Next in interesting, we've all had to read books we don't like in school and we all know how miserable that can be. I also had to read (all the way to the end) some books I didn't like, but it was a very different experience. Because I volunteered for this panel and because I felt a responsibility to the other panelists and because I felt a responsibility to the authors, the misery of slogging through an awful book in order to turn in a half-assed book report so your parents don't get mad at you for a bad grade, was not present. There really were times when a good old fashioned read-it-while-blacked-out was pretty appealing. But that school room angst wasn't there. The pressure to do this reading came only from myself and so it was easier to transition my reading experience from debilitating agony to the observation of my debilitating agony in an attempt to extract something useful about life, the universe, and everything from these awful, awful books.

The Big Wrap Up

Given the length of this post, I'll post about my two favorite books later (I believe this is what they call in the business a “teaser.”), but it seems like I should come to some conclusions. Here they are in list form.

All told it was fun and challenging book binge, the piled remnants of which I still have no idea what to do with. What did you do on your summer vacation?

|

| The Finished |

Your favorite author was once a debut author. Everyone's favorite author was once a debut author. But debut authors are a big risk for publishers. There are so many unknowns that go into signing and publishing an author for the first time and every one of those unknowns is a potential monetary loss. There's a chance said author will receive good review coverage, but there's a better chance the limited (in some ways) review coverage will go to an author the reviewer does not need to spend text introducing to the public. There's a chance a solid author tour will garner attention, that galleys of the book will get in the right hands and those hands will actually open said galleys so the eyes can eat the words, that the word of mouth support will be enough to at least see the bottom line and to establish some presence in the minds of the book buying public so the next book will get much more exposure, but it is more likely few people will go to debut author events, the galleys won't get opened, and the book won't sell enough to recoup the investment. But every great, guaranteed best-seller was once a debut, so publishers continue to take the risk.

But with publishing margins slimmed by a whole host of different economic and social forces, it wouldn't be that surprising to see publishers taking fewer risks and publishing fewer debut authors. You wonder if publishers will be willing to endure the sales of, for example, Ann Patchett's first book, no matter how much they believe in the talent of the author. (Fewer books being published in the traditional way would probably be a good thing, but not for this reason and that's a different post anyway.(And, of course, they're still one book short.)) This panel shows that not only are publishers committed to publishing debut authors (each publisher could only submit three titles), but they are finding cost-effective ways to support those debut authors. With so much of our book economy making so much of traditional publishing more difficult, (i.e. as the necessary capital is squeezed out of publishing by lower margins and lower sales) it is exciting to see publishers taking steps to make sure they continue what may be their most bottom-line damaging responsibility.

The Bad

|

| The Read-a-Bunch-Of |

So those bottom lines? Man, keeping those lights on and shit, huh? As publishers struggle, one of the concerns in the readerly world, is that they will skimp on editing; not proofreading, but that process by which a work of potential genius is improved, idea by idea, character by character, chapter by chapter, sentence by sentence, word by word into a work of actual genius; that weird alchemical art that discerns the potential of a work of literature and then induces the writer to reach that potential; the long, labor intensive, and thus, in many ways, expensive process, that can be a vital part of producing great works of human culture. That editing. And given that there is absolutely no correlation between quality and sales, one could not blame a publisher, or at least an accountant who works for a publisher, for asking whether it is really worth the cost to make a good work great.

But it is almost impossible to figure out whether capital restrictions are lessening the quality of published books. There just isn't a way to create any kind of meaningful data about un-reached potential. However, an alarming number of books I read for this panel, including a few I really liked, had very strong beginnings, and a marked tapering off in quality by the end. To put this another way; the chapters that would land an agent, and the chapters that an agent would use to get a contract, and the chapters likely to earn a purchase at the bookstore, were excellent while the rest tended to be mediocre. And what I saw were not issues of copy editing or proofreading (which are forgiven in galleys), but fundamental questions on the direction of the stories and the development (or not) of the characters and themes. In short, a solid number of the submitted books seemed to suffer from a lack of editing, the important editing that makes a good work great.

As I said, this doesn't really mean there is a trend of diminishing editing in publishing. Maybe the time and money was spent and what was produced really had reached its potential. Maybe the particular editors themselves weren't great editors. Maybe great advice was not taken. Maybe each book in which I saw this issue has its own perfectly rational explanation and this concern is totally unfounded. Still, a pattern is a pattern and it was a troubling pattern.

The Interesting

|

| The Cat (Unreadable) |

Next in interesting, we've all had to read books we don't like in school and we all know how miserable that can be. I also had to read (all the way to the end) some books I didn't like, but it was a very different experience. Because I volunteered for this panel and because I felt a responsibility to the other panelists and because I felt a responsibility to the authors, the misery of slogging through an awful book in order to turn in a half-assed book report so your parents don't get mad at you for a bad grade, was not present. There really were times when a good old fashioned read-it-while-blacked-out was pretty appealing. But that school room angst wasn't there. The pressure to do this reading came only from myself and so it was easier to transition my reading experience from debilitating agony to the observation of my debilitating agony in an attempt to extract something useful about life, the universe, and everything from these awful, awful books.

The Big Wrap Up

Given the length of this post, I'll post about my two favorite books later (I believe this is what they call in the business a “teaser.”), but it seems like I should come to some conclusions. Here they are in list form.

I would totally read for a prize/panel again.

Being forced to read what you would not normally read every now and then is a very good thing.

Indie booksellers have, perhaps, the ideal mix of passion and reasonableness. Seriously, there were exchanges that went something like “I will cut myself in visible places if this book is not included in the top ten, but I've got to get back on the floor so if everybody else is OK with cutting it, I'm cool with cutting it.” How about we govern for a bit?

New art is still being written...

but much more new entertainment is still being written...

which is fine...

though I'd really like to see a little more art.

All told it was fun and challenging book binge, the piled remnants of which I still have no idea what to do with. What did you do on your summer vacation?

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)