Victor Lavalle is one of my favorite living writers. Like Edgar Allen Poe, he is able to layer weirdness on top of weirdness so that, as you dig through the monsters and the radical suicide death cults and the mysterious librarians, you find it's our real obsession with higher powers and our real attitudes toward mental health that are truly strange.

His new book, The Ballad of Black Tom is an homage to the work of H.P. Lovecraft (based primarily on "The Horror at Red Hook") that draws elements from Lovecraft's entire ouvre into a story about a young black man from Harlem trying to make his way in the world. In some ways, Lovecraft is as influential to horror writing as Tolkien is to fantasy writing, providing a lexicon, a fundamental structure, and a mythology that horror writers still use today. Lovecraft was also racist. And not older-relative-after-a-few-glasses-of-wine-at-Thanksgiving racist; he was hatefully, maliciously racist.

Lavalle has talked about what it means to be an African American author writing an homage to a racist so I don't need to here, but I think he does something interesting that reveals one of the powerful, critical aspects of homage. Homage can be more than just a celebration, more than just a retelling, more than just a depositing of a story or style in a new place or time (though all of those are fun, important aspects of homage). Homage also allows authors to critique those past works, turning up the volume on certain traits, emphasizing certain ideas, elucidating aspects that are not otherwise obvious, and even re-appropriating the works for different, even opposed purposes.

What made Lovecraft's work powerful, and what still resonates in the horror genre today, is the idea of another world of unseen forces pushing us this way and that through life. Whether it was magic, Cthulhu, or some other mysterious force, the characters in Lovecraft's stories were subject to forces vastly more powerful than they were that determined the course of their lives or even their deaths. We might feel as though we are in control, we might even believe we can harness some of those powerful forces, but that is only because we haven't dug far enough into the basement, sailed far enough into the ocean, looked deep enough into the eyes of the stranger. Lovecraft made daily life's simple anxieties visceral, bodily, and horrifying. Lavalle's homage taps into that existential anxiety, but by twisting it ever so slightly, by setting it partially in Harlem and by making one of the protagonists a young African American man, Lavalle has revealed an aspect of Lovecraft's unseen forces that Lovecraft himself never saw.

At one point, Tom comes home to find that his father has been murdered by the police. Tom's apartment was searched in connection to an investigation and one of the investigators saw Tom's father with a guitar, assumed it was a gun, shot him six times, and—because the officer “feared for his life”—reloaded his revolver and shot five more times. For most people, for pretty much everyone in this country who is not a straight white cisgendered man born in America, those mysterious powerful forces casually dealing death and destruction, those otherworldly beings, those dark underground cabals deciding the fate of those they do not regard as worthy of dignity are real. They are not forces of magic or hauntings or Cthulhu, they are institutional racism, systems of power, and the residual structures of colonialism. They are Jim Crow, mass incarceration, and 75 cents on the dollar. In some ways this really isn't even a metaphor. If a magic spell is a string of words able to bring about some kind of corporeal action, “Hello, police, there's a man in my neighborhood, um, he's tall and black” might be America's deadliest spell. Is there any ritual that signals the loss of one's personal agency more than the chanting of “Stop resisting?” I mean, the Klu Klux Klan leaders call themselves wizards and dragons for fuck's sake.

What is most interesting to me about this is how otherwise faithful to Lovecraft The Ballad of Black Tom is. The creeping unease. The protagonist in way, way over his head. The magic. The monsters. The skin of the universe peeled back for just a second to reveal the contorted organs of being beyond our conception. And yet twist it all just ever so slightly, and an entirely new conversation is created. Lavalle has been utterly faithful to Lovecraft and told a story that would've horrified him.

To me, this is where the real power in literature resides. All books are only semi-stable. Though the words on fixed on the page, the efforts of readers give them vitality, make them move, transform them into something (and some things) beyond the imagination of the individual creator. The act of writing is powerful and flexible enough that a potent reader can transform the work of a malignant racist into a statement on the experience of institutional racism. No story is ever really dead. No work of literature ever irredeemable. The Ballad of Black Tom begins with Tom delivering a magic book, which in its complete form would give the reader the complete magic alphabet and access to unspeakable power. Of course, we already have the complete alphabet and when it's used by a writer and reader like Victor Lavalle every book is magic.

Showing posts with label Reviews. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Reviews. Show all posts

Friday, March 4, 2016

Monday, September 14, 2015

Valeria Luiselli's Delightful Post-Modernism

Post-modernism is in a weird place. It's been declared dead for a decade or more, and yet there is still plenty of interesting work being done in the ground it broke. Actually, that part's not weird. I'd argue there are still plenty of Romantics writing today, plenty of Victorians, even more Modernists, and more Medievalists than I feel comfortable considering. As handy as it is for structuring syllabi, survey courses, and textbooks, literary and artistic movements aren't strictly delineated. But even given that standard-issue, chaos-of-existence inherent weirdness, Post-Modernism is still in a weird space. (Postmodernism? You guys have a hyphenation preference?) We all kind of accept that something new needs to replace it, and yet I don't think there's evidence that any particular philosophy or aesthetic has congealed into an identifiable replacement. Add in the fact that the very nature of post-modernism tore down the structures that are usually used to build, identify, and study literary movements, and you get to a very weird place.

But even though post-modernism is a weird place, or perhaps because it's in such a weird place, a lot of good writing is still coming out of it. Cesar Aira, Mark Z. Danielewski, Kate Zambrano, Blake Butler, and Karen Tei Yamashita (have I written that post about why I Hotel should be considered one of the great giant-post-modern novels along with Infinite Jest, Underworld, Gravity's Rainbow, The Recognitions, Deflategate, and Kim Davis walking out of jail to “Eye of the Tiger?” I'll add it to the list) all spring to mind. And, of course, a few of post-modernism's avatars like Thomas Pynchon and Lydia Davis are still kicking it. Furthermore, not every reader has caught up to post-modernism yet (Shit, not every reader has caught up to modernism yet) and not all the problems in our culture that post-modernism (see above) addresses have been solved, so it's only natural, if weirdly so, for writers and readers to continue the post-modern project even as we concurrently tear it to bits in order to replace it.

In her first two novels, Valeria Luiselli is continuing that post-modern project. Her debut, Faces in the Crowd, featured the author as character, a shifting perspective, problems of authenticity, fraud, and consideration of the nature of art, identity and narrative. Her new book, The Story of My Teeth, is, in many ways, even more archetypally post-modern as it is a collaborative work that complicates the idea of authorship (Luiselli collaborated on it with the workers in a juice factory), structured around a made-up system of categorization, that examines consumerism, appropriation, the cult of celebrity, and the meaning of objects, while referencing art, literature, and history. One of the sections is even a chronology of events assembled by the book's translator. At one point, the main character auctions off himself, to help support a church he doesn't particularly believe in, to his own estranged son. You could almost hear Pynchon kicking himself for not coming up with something like that.

But even if she is continuing the post-modern project, Luiselli's work is different. Her work is not paranoid, corrosively ironic, or toxicly nihilistic. Though post-modernism's decades-long sneer at convention was, in my opinion, productive, vital, and often satisfying and entertaining, it has run it's course. Luiselli doesn't sneer. She grins. In Luisellis' work all the anger, the frustration, and the powerlessness that defined earlier post-modernism, are replaced by delight.

Though present in Faces in the Crowd, especially in the voice of the narrator's child, The Story of My Teeth might be the most delightful book I've read in ages. The delight starts with Highway and the opening sentences; “I'm the best auctioneer in the world, but no one knows it because I'm a discreet sort of man. My name is Gustavo Sanchez Sanchez, though people call me Highway, I believe, with affection.” From there Highway tells us the story of his rise and fall, his marriage and divorce, his estrangement and reconciliation with his son (which naturally involved Highway being locked in a really creepy clown-based multimedia art piece that actually exists), his acquisition of the teeth of celebrities and his auctioning of the teeth of celebrities, and, of course, the philosophy of auctioneering he received from the “grandmaster auctioneer and country singer, Leroy Van Dyke.” Through all his ups and downs, all his triumphs and failures, Highway maintains that same “I am a discreet sort of man,” voice. Despite or because of the weirdness or even silliness of the story, the book is a joy to read and that joy remains no matter how critically you might delve into the book's headier ideas.

The best concerts are those where the musicians seem to be having as much fun as the audience. To me, there is something infectious and exhilarating in watching someone in love with what they are doing. Somehow, Luiselli makes it seem as though the person most delighted by Highway, his antics, his philosophy, his auctions, his bravado, the contorted references to other literature, with the images in the back of the book including a Google Maps image of Disneylandia, the use of art, the intrepid potential biographer, and the play of cultural attribution, narrative, and language, is Luiselli herself. All writers love to write. It wouldn't be worth it if we didn't. Very few writers, however, find a way to demonstrate that love at all and even fewer do it so overtly, so joyously, and so, well, delightfully, as Valeria Luiselli does in The Story of My Teeth.

Post-modernism has spent a lot of time and energy tearing down. I like to think of it as an un-fettering process, in which the ideologies most easily leveraged by systems of power to control the creation and interpretation of art were torn away, leaving the artist totally free to approach the content and method of her art. Since we have deconstructed, now we get to reconstruct. I don't know what we're going to build in the open space created by post-modernism but I think we should all be grateful, that Valeria Luiselli, at least, is going to build a playground.

But even though post-modernism is a weird place, or perhaps because it's in such a weird place, a lot of good writing is still coming out of it. Cesar Aira, Mark Z. Danielewski, Kate Zambrano, Blake Butler, and Karen Tei Yamashita (have I written that post about why I Hotel should be considered one of the great giant-post-modern novels along with Infinite Jest, Underworld, Gravity's Rainbow, The Recognitions, Deflategate, and Kim Davis walking out of jail to “Eye of the Tiger?” I'll add it to the list) all spring to mind. And, of course, a few of post-modernism's avatars like Thomas Pynchon and Lydia Davis are still kicking it. Furthermore, not every reader has caught up to post-modernism yet (Shit, not every reader has caught up to modernism yet) and not all the problems in our culture that post-modernism (see above) addresses have been solved, so it's only natural, if weirdly so, for writers and readers to continue the post-modern project even as we concurrently tear it to bits in order to replace it.

In her first two novels, Valeria Luiselli is continuing that post-modern project. Her debut, Faces in the Crowd, featured the author as character, a shifting perspective, problems of authenticity, fraud, and consideration of the nature of art, identity and narrative. Her new book, The Story of My Teeth, is, in many ways, even more archetypally post-modern as it is a collaborative work that complicates the idea of authorship (Luiselli collaborated on it with the workers in a juice factory), structured around a made-up system of categorization, that examines consumerism, appropriation, the cult of celebrity, and the meaning of objects, while referencing art, literature, and history. One of the sections is even a chronology of events assembled by the book's translator. At one point, the main character auctions off himself, to help support a church he doesn't particularly believe in, to his own estranged son. You could almost hear Pynchon kicking himself for not coming up with something like that.

But even if she is continuing the post-modern project, Luiselli's work is different. Her work is not paranoid, corrosively ironic, or toxicly nihilistic. Though post-modernism's decades-long sneer at convention was, in my opinion, productive, vital, and often satisfying and entertaining, it has run it's course. Luiselli doesn't sneer. She grins. In Luisellis' work all the anger, the frustration, and the powerlessness that defined earlier post-modernism, are replaced by delight.

Though present in Faces in the Crowd, especially in the voice of the narrator's child, The Story of My Teeth might be the most delightful book I've read in ages. The delight starts with Highway and the opening sentences; “I'm the best auctioneer in the world, but no one knows it because I'm a discreet sort of man. My name is Gustavo Sanchez Sanchez, though people call me Highway, I believe, with affection.” From there Highway tells us the story of his rise and fall, his marriage and divorce, his estrangement and reconciliation with his son (which naturally involved Highway being locked in a really creepy clown-based multimedia art piece that actually exists), his acquisition of the teeth of celebrities and his auctioning of the teeth of celebrities, and, of course, the philosophy of auctioneering he received from the “grandmaster auctioneer and country singer, Leroy Van Dyke.” Through all his ups and downs, all his triumphs and failures, Highway maintains that same “I am a discreet sort of man,” voice. Despite or because of the weirdness or even silliness of the story, the book is a joy to read and that joy remains no matter how critically you might delve into the book's headier ideas.

The best concerts are those where the musicians seem to be having as much fun as the audience. To me, there is something infectious and exhilarating in watching someone in love with what they are doing. Somehow, Luiselli makes it seem as though the person most delighted by Highway, his antics, his philosophy, his auctions, his bravado, the contorted references to other literature, with the images in the back of the book including a Google Maps image of Disneylandia, the use of art, the intrepid potential biographer, and the play of cultural attribution, narrative, and language, is Luiselli herself. All writers love to write. It wouldn't be worth it if we didn't. Very few writers, however, find a way to demonstrate that love at all and even fewer do it so overtly, so joyously, and so, well, delightfully, as Valeria Luiselli does in The Story of My Teeth.

Post-modernism has spent a lot of time and energy tearing down. I like to think of it as an un-fettering process, in which the ideologies most easily leveraged by systems of power to control the creation and interpretation of art were torn away, leaving the artist totally free to approach the content and method of her art. Since we have deconstructed, now we get to reconstruct. I don't know what we're going to build in the open space created by post-modernism but I think we should all be grateful, that Valeria Luiselli, at least, is going to build a playground.

Monday, September 22, 2014

Impossible to Review

My goal in reviewing a book is to give readers the information they need to decide whether or not they want to read the book, which means I describe the dominant characteristics of the book, while assessing its execution with my, subjective obviously, opinion of quality. Sometimes that also involves placing the book in its historic or literary context, sometimes that means offering some interpretations of the work, and sometimes that means describing more general aspects of literature. My hope, is that I have written enough decision making resources into the review that a reader can decide they really want to read a book I have described as a book I don't think anyone should read. As much as I think Michiko Kakutani generally has regressive taste in books, I always know exactly what my relationship to a book she's reviewed is likely to be.

But not all books have the same “reviewability.” Here are three categories of books that are damn near impossible to review.

Abominations of the Written Word

|

| My actual tongue burst into flames reading those words. |

Part of solving this problem is to give those books the same attention you give to books you like, which is why you almost never seen a bad review on my blog. If reading a book makes me want to peel the first few layers of skin off my fingertips with a vegetable peeler and cartwheel dots of blood down the middle of the street, I'm going to stop reading it. And if I stop reading it, I won't be able to write with that respect. If I've committed to reviewing a book for someone else, I'll pick up my eyes, get through, and do my best to be truthful and respectful at the time. I've had editors decide that I did not strike that right balance and chose not to run those reviews, which is what an editor is supposed to do. The reviews have also been run without additional comment. Sure, at the end of writing those reviews, there is a sense of having scaled a mountain that was also kicking you in the junk while you climbed, but there is also a sense of wishing to have spent your time not getting kicked in the junk.

Towering Achievements of Literature

|

| My brain has been shredded by this book's razor-sharp awesome. |

What distinguishes this challenge from writing about weeping pustules of “language” is that I want to write about these books, I want to celebrate them, I want to make other people read them. It is a beautiful enthusiasm but sometimes it means what is supposed to be a review becomes publicity.

Twice, recently, I've started to review a book only to get to the other side of a first draft and realize there would be no way I could mangle my personal reading experience into a review and wrote essays instead. One of them was this essay on Karl Ove Knaussgaard's absolutely brilliant but at times Revelations-level infuriating My Struggle Volume 2: Man in Love, and the other an essay on White Girls by Hilton Als. But that only works when I have the luxury to not turn in a review. When I've committed to a review I try my best to be overt as to who I am as a reader so readers understand how such a powerful connection was made and to, at least, mention aspects of the book other readers might have a different reaction to.

Meh.

Is there a more horrible and yet more expressive word in our modern lexicon? (I'm sure there's someone cranking out a self-help book about removing “meh” from your life.) There's nothing wrong with the book, per se, I mean, it's fine, it's just, well...there isn't a lot you can say about a book that is “meh.” So, maybe you summarize the plot or the themes, maybe suggest some other works this one might resemble, and then, well, you tell the world the book is “meh.”

Is there a more horrible and yet more expressive word in our modern lexicon? (I'm sure there's someone cranking out a self-help book about removing “meh” from your life.) There's nothing wrong with the book, per se, I mean, it's fine, it's just, well...there isn't a lot you can say about a book that is “meh.” So, maybe you summarize the plot or the themes, maybe suggest some other works this one might resemble, and then, well, you tell the world the book is “meh.” In some ways this is analogous to the respect problem of the books that set my spleen on fire with their incendiary awful. Does a 300 word review really demonstrate respect for an act of human creation? Does it show that I have done my due diligence as a reviewer? Does it do anything for the reader of the review? I mean, ultimately, the review should make the reader look away from it, to the book under consideration, but the review is still read and the act of reading it should have value. To often, I feel the review prose at the other end of a meh book tends, itself, to be meh.

What Is a Book Review?

Perhaps one of the most frustrating and perhaps even destructive aspect of our current literary culture is our lack of distinction between a book review and what gets appended to books by casual readers at Amazon and Goodreads. I'm not disparaging those casual reviews, at all, as they do serve their purpose and a reader who knows how to utilize them can extract a lot of useful information from them. But they are different from what we have traditionally called “book reviews.”

Book reviews are not just an expression of taste or opinion, though they do express taste and opinion, and book reviews are not just an assessment of quality, though they do that as well; book reviews are a cultural conversation between writers and readers, a conversation that has the ability to extend itself beyond the book in question to examine other aspects of being a person. They are a vital part of the give and take that is created by a book being written, and they extend that give and take beyond the individual reader with the individual book, to the entire world of readers.

The short opinions and ratings systems of Amazon and Goodreads are a kind of conversation about books, and, though I, personally, don't get a lot of value or information from that kind of conversation, I'm not upset that other readers do. But those comments do not do what book reviews do. They don't help us become better readers. They don't give us insight into the potential meaning of a book. They don't connect that book to the history and future of books. They don't make us think about the world around us. And they certainly don't slow down our judgment machines showing us the time, complexity, and thought that should go into forming an opinion.

Apologies for getting a little ranty here at the end, but we should have more book reviews and they should be in the mainstream media. The literary internet is amazing and powerful, and passionate, thoughtful, and intelligent readers have done much to fill the void in our culture when newspapers and other mainstream media dropped books coverage. (Quick aside: People read newspapers, readers want to know about books, so obviously, the first thing you cut from your newspaper is your books coverage, because obviously if they're reading a newspaper they don't have any interest in reading about things to read.) But the literary internet cannot replace the casual, tangential, part-of-the-habitat interaction with literature that happens in newspapers and magazines, where people reading for the sports scores are at least shown that books count in our culture.

So even though some books are impossible to review (phew, brought it back around) we still need more book reviews in more places for more people. Unless of course, we don't want to run the risk of having a more thoughtful culture.

Wednesday, February 19, 2014

Some Books Are Impossible to Review

|

| Judging |

But not all books have the same “reviewability.” Here are three categories of books that are damn near impossible to review.

Abominations of the Written Word

No matter how bad a book is, it is still an act of human creation and, thus, still deserves to be treated with a level of respect. But how do you communicate that respect while also describing a reading experience where you wanted to pull out your eyes with sauce sodden sporks and roll them back and forth between your hands while sitting on the floor waiting for the searing pain in your brain to leech out your newly opened face hatches? As a reviewer, you have to be honest when you don't like a book, because that allows you to be honest when you like a book, and as a writer, you have to use the most compelling language you can come up with, but you are also a human being discussing something very important to another human being.

Part of solving this problem is to give those books the same attention you give to books you like, which is why you almost never seen a bad review on my blog. If reading a book makes me want to peel the first few layers of skin off my fingertips with a vegetable peeler and cartwheel dots of blood down the middle of the street, I'm going to stop reading it. And if I stop reading it, I won't be able to write with that respect. If I've committed to a reviewing a book for someone else, I'll pick up my eyes, get through, and do my best to be truthful and respectful at the time. I've had editors decide that I did not strike that right balance and chose not to run those reviews, which is what an editor is supposed to do. The reviews have also been run without additional comment. Sure, at the end of writing those reviews, there is a sense of having scaled a mountain that was also kicking you in the junk while you climbed, but there is also a sense of wishing to have spent your time not getting kicked in the junk.

Towering Achievements of Literature

|

| Judging |

What distinguishes this challenge from writing about weeping pustules of “language” is that I want to write about these books, I want to celebrate them, I want to make other people read them. It is a beautiful enthusiasm but sometimes it means what is supposed to be a review becomes publicity.

Twice, recently, I've started to review a book only to get to the other side of a first draft and realize there would be no way I could mangle my personal reading experience into a review and wrote essays instead. One of them was this essay on Karl Ove Knaussgaard's absolutely brilliant but at times Revelations-level infuriating My Struggle Volume 2: Man in Love, and the other an essay on White Girls by Hinton Als, which I've been teasing on twitter and will hopefully be here in the not-to-distant future. But that only works when I have the luxury to not turn in a review. When I've committed to a review I try my best to be overt as to who I am as a reader so readers understand how such a powerful connection was made and to, at least, mention aspects of the book other readers might have a different reaction to.

Meh.

|

| Judging harshly. Very harshly, indeed. |

In some ways this is analogous to the respect problem of the books that set my spleen on fire with their incendiary awful. Does a 300 word review really demonstrate respect for an act of human creation? Does it show that I have done my due diligence as a reviewer? Does it do anything for the reader of the review? I mean, ultimately, the review should make the reader look away from it, to the book, but the review is still read and the act of reading it still should have value. I feel the review prose at the other end of a meh book tends, itself, to be meh.

What Is a Book Review?

Perhaps one of the most frustrating and perhaps even destructive aspect of our current literary culture is our lack of distinction between a book review and what gets appended to books by casual readers at Amazon and Goodreads. I'm not disparaging those casual reviews, at all, as they do serve their purpose and a reader who knows how to utilize them can actually get quite a lot of useful information from them. But they are different from what we have traditionally called “book reviews.”

Book reviews are not just an expression of taste or opinion, but they do both, and book reviews are not just an assessment of quality, though they do that as well; book reviews are a cultural conversation between writers and readers, a cultural conversation that has the ability to extend itself beyond the book in question to examine other aspects of being a human being. They are a vital part of the give and take that is created by a book being written, and they extend that give and take beyond the individual reader with the individual book, to the entire world of readers.

The short opinions and ratings systems of Amazon and Goodreads are a kind of conversation about books, and, though I, personally, don't get a lot of value or information from that kind of conversation, I'm not upset that other readers do. But those comments do not do what book reviews do. They don't help us become better readers. They don't give us insight into the potential meaning of a book. They don't connect that book to the history and future of books. They don't make us think about the world around us. And they certainly don't slow down our judgment machines showing us the time, complexity, and thought that should go into forming an opinion.

Apologies for getting a little ranty here at the end, but we should have more book reviews and they should be in the mainstream media. The literary internet is amazing and powerful, and passionate, thoughtful, and intelligent readers have done much to fill the void in our culture when newspapers and other mainstream media dropped books coverage. (Quick aside: People read newspapers, readers want to know about books, so obviously, the first thing you cut from your newspaper is your books coverage, because obviously if they're reading a newspaper they don't have any interest in reading about things to read.) But the literary internet cannot replace the casual, tangential, part-of-the-habitat interaction with literature that happens in newspapers and magazines, where people reading for the sports scores are at least shown that books count in our culture.

So even though some books are impossible to review (phew, brought it back around) we still need more book reviews in more places for more people. Unless of course, we don't want to run the risk of having a more thoughtful culture.

Monday, January 27, 2014

Review of Silence Once Begun

The image that came to mind when I started reading Silence Once Begun was of a performer setting up a massive plate-spinning act; hundreds of plates across a massive multi-tiered stage, with complex lighting, beautiful assistants, and a live orchestra. This is not a particularly unique experience in contemporary fiction that pays attention to all of the experiments and achievements of previous authors; after the structural, stylistic, and prosaic experiments and performances of modernism and post-modernism, a sense of daring and risk, a sense that at any moment it could all spectacularly collapse, bringing the stage, the pit, and the first three rows with it, should be assumed in literature. What was different about Silence, was I wasn't sure whether I wanted to see the plates spin or shatter. There is joy in watching the brilliantly complex unify itself into a brilliant simplicity (think Wallace, Danielewski, Egan) but there is also joy in watching the brilliantly complex totally fucking explode (think Pynchon, Blake Butler). Of course, one of the reasons I love Jesse Ball's work so much is how baffling and unexpected it can be. Though his previous two novels, The Way Through DoorsThe Curfew and , were more powerful in-the-moment-of-reading experiences there is something uniquely lingering about Silence Once Begun. By the end of the novel, Ball made the plates disappear.

The plot is relatively simple; after losing a bet, a young man signs a confession for a sensational crime he did not commit. He is tried, convicted, and executed. He remains silent for almost the entirety of his incarceration. Years later, a journalist named Jesse Ball, interviews the young man's family, “friends,” and a few of the public figures involved in the case, in part, to come to some understanding of the case and in part to better understand his disappearing relationship with his wife. From the plot Silence Once Begun could be about pretty much anything; justice, family, truth, identity, the power of language, the role of absence in all of the above, and yet is also seems to dismiss all of those themes and perhaps even the idea of themes all together. "Of silence, I can say only what I heard, that all things are known by that which they make or leave--and so speech isn't itself, but its effect, and silence is the same.” (186) So we are not really reading a book, so much as reading what the book makes or leaves within us.

The crime itself doesn't offer much thematic guidance to the reader; a series of mysterious disappearances of mostly elderly people in a single neighborhood with absolutely no evidence whatsoever of the kidnapper. No witnesses, no forensic evidence, no signs of forced entry. The only clue at each scene was a single card. The disappeared could represent anything you think has disappeared. And once the crime itself is described, it drops from the narrative. It is present, but somehow, you get the sense any crime could have been the crime; the point was elsewhere.

All of which makes this a very hard book to review. How do I communicate to you, in a way that is useful in your book decision making processing, the nature of this book, if I have very little sense of it myself? How do I access the quality of the book or give you to the tools to guess the quality of the book in relation to your taste, if I can't really tell you what it is about? For some readers, that's a ringing endorsement. For others, they might not be so sure. To make things stranger, this whispering, haunting, phantasm of a novel will be Ball's first hardcover release with perhaps the most marketing and publicity devoted to it by the publisher of any of his books. Someone thinks this is going to be his breakout book. I certainly hope it is.

And then there's the conclusion. Like the author's note at the end of The Handmaid's Tale, the conclusion to Silence reverberates back through the text, changing the value of the events we see. It isn't just that we get the actual villain's reasons for the crime and it isn't really that the mystery is explained. Instead there is, perhaps (and that “perhaps” might be what ensures Ball is read for decades to come), a powerful and pervasive statement about society in general. There's a chance that for all the focus on the emotions and personal relationships of the scenario; the book was actually always about justice. Or indifference. Or...something else. There is a chance that Ball not only made the plates disappear, but the stage as well.

The plot is relatively simple; after losing a bet, a young man signs a confession for a sensational crime he did not commit. He is tried, convicted, and executed. He remains silent for almost the entirety of his incarceration. Years later, a journalist named Jesse Ball, interviews the young man's family, “friends,” and a few of the public figures involved in the case, in part, to come to some understanding of the case and in part to better understand his disappearing relationship with his wife. From the plot Silence Once Begun could be about pretty much anything; justice, family, truth, identity, the power of language, the role of absence in all of the above, and yet is also seems to dismiss all of those themes and perhaps even the idea of themes all together. "Of silence, I can say only what I heard, that all things are known by that which they make or leave--and so speech isn't itself, but its effect, and silence is the same.” (186) So we are not really reading a book, so much as reading what the book makes or leaves within us.

The crime itself doesn't offer much thematic guidance to the reader; a series of mysterious disappearances of mostly elderly people in a single neighborhood with absolutely no evidence whatsoever of the kidnapper. No witnesses, no forensic evidence, no signs of forced entry. The only clue at each scene was a single card. The disappeared could represent anything you think has disappeared. And once the crime itself is described, it drops from the narrative. It is present, but somehow, you get the sense any crime could have been the crime; the point was elsewhere.

All of which makes this a very hard book to review. How do I communicate to you, in a way that is useful in your book decision making processing, the nature of this book, if I have very little sense of it myself? How do I access the quality of the book or give you to the tools to guess the quality of the book in relation to your taste, if I can't really tell you what it is about? For some readers, that's a ringing endorsement. For others, they might not be so sure. To make things stranger, this whispering, haunting, phantasm of a novel will be Ball's first hardcover release with perhaps the most marketing and publicity devoted to it by the publisher of any of his books. Someone thinks this is going to be his breakout book. I certainly hope it is.

And then there's the conclusion. Like the author's note at the end of The Handmaid's Tale, the conclusion to Silence reverberates back through the text, changing the value of the events we see. It isn't just that we get the actual villain's reasons for the crime and it isn't really that the mystery is explained. Instead there is, perhaps (and that “perhaps” might be what ensures Ball is read for decades to come), a powerful and pervasive statement about society in general. There's a chance that for all the focus on the emotions and personal relationships of the scenario; the book was actually always about justice. Or indifference. Or...something else. There is a chance that Ball not only made the plates disappear, but the stage as well.

Wednesday, November 13, 2013

Review of Seiobo There Below

Seiobo There Below does not use expected grammar. Those look like sentences, but they are not. Those blocks of texts look like paragraphs but, with a few exceptions, they are not. Yes, there is every indication that this book is organized in chapters, but I do not believe those are chapters. We have to borrow from other modes of expression to describe the grammar of Seiobo. It could be organized into stanzas and lines. Or perhaps lines, scenes, and acts. Those are better, but still not quite accurate. Seiobo There Below is a symphony; it is written in instrument sections, movements, solos, fugues...and the impossibility of Seiobo is that it is designed to be experienced as you would listen to a symphony; hearing all of the different parts come together. Or maybe its a painting, with the “sentences,” “paragraphs,” and “chapters,” as canvas, color and brushstroke, and again, we are somehow supposed to “see” the totality even though we can only read it in its separate parts.

Seibo There Below opens with an image of a Kamo-hunter, a crane or heron like bird standing in the river, and the entire opening chapter, entitled “The Kamo-hunter,” is just that bird standing in that river while time exists within and around it. I believe this passage acts like the first 70 or so pages in In Search of Lost Time, setting up all of the ideas and themes of the symphony, both in its content (fair warning, there is a lot of nothing happening) and in its style. You'll know pretty quickly whether Seiobo is a book for you. For me I was enraptured immediately by the prose; “Everything around it moves, as if just this one time and one time only, as if the message of Heraclitus has arrived here though some deep current, from the distance of an entire universe, in spite of all the senseless obstacles, because the water moves, it flows, it arrives, and cascades;...” The rhythm. The precision. The obsessive doubling and tripling and quadrupling back over scenes and images to put every detail in its perfect place; or at least, put details in places where they draw the eye of the reader so as to create an opportunity for mystery; an Acropolis whose hill you can climb but whose place you can never reach and then you get hit by a car.

The obsessiveness of Laszlo's prose naturally finds itself drawn to express obsessive actions, which, also pretty naturally, sets much of the action in Japan where precision is an end in itself. We see the restoration of a sacred Buddha statue, the carving of a Noh mask (I highly recommend Kissing the Mask by William Vollman, a critical study on Noh theater and femininity which could almost be read as a companion piece to Seiobo), and the cyclical rebuilding of a Shinto shrine and the ritual of cutting down the trees used to build it. But we also see the preparation of a panel for an altar in Renaissance Europe (which is insane), the construction of a Renaissance dowry box, and the copying of a legendary Andrei Rublev icon, all with such an intensity of precision that you are left feeling as though you have learned everything you could ever learn about the topic, while understanding nothing about it. (Oh, and a homeless guy buys a sharp knife in Barcelona, because reasons.)

This tension between knowledge and understanding, between erudition and meaning, between precision and communication reinforces the tension between the temporal experience of physically reading the book and unified experience it strives for. The movement about rebuilding the shrine climaxes when a native of Kyoto who had been acting as a guide for a Western journalist friend, hikes the friend to the top of a small mountain with a panoramic view of Kyoto at night. The Western journalist concludes the exact opposite of what his Japanese guide intended. Another way to describe Seiobo There Below is a symphony in words in opposition to the opposition to that moment of opposition. (Yeah, I'm going to go with that.) Or perhaps it just is and is about the impossibility of perfection. Or something else perfectly unified and perfectly divided.

Like Everything Matters! which is one of the most sincerely optimistic books I've ever read that also happens to be about the apocalypse, Seiobo There Below is one of the most sincerely cynical books I've ever read that also happens to be about beauty. It is a beautifully written obsession with beauty that finds at the end of its obsession...something that is not beauty. An empty box. The mask for a monster. A painting never completed. A very sharp knife purchased by a man who cannot afford it. The one time you don't look both ways before crossing the street. The relentless hollowness of ever lasting life. A long-legged raptor in a river.

Seiobo There Below is one of those absolutely brilliant, absolutely beautiful, absolutely stunning books, I have a difficult time recommending at the bookstore. For reasons I can totally understand, a lot of people simply will not or don't want to deal with sentences this long or feel they require an actual story arc to get into a book, or have a details limit after which something better fucking happen or they are totally tapping out. It's not a book you can put in a stranger's hands. But it is a beautiful book. And, in some ways, it is the most thorough and most direct study of beauty I've ever read. And if you have wondered about the process and statement of beauty, Seiobo There Below is a hill you should climb whether the “Acropolis” on top is the “Acropolis” in your mind or not.

Seibo There Below opens with an image of a Kamo-hunter, a crane or heron like bird standing in the river, and the entire opening chapter, entitled “The Kamo-hunter,” is just that bird standing in that river while time exists within and around it. I believe this passage acts like the first 70 or so pages in In Search of Lost Time, setting up all of the ideas and themes of the symphony, both in its content (fair warning, there is a lot of nothing happening) and in its style. You'll know pretty quickly whether Seiobo is a book for you. For me I was enraptured immediately by the prose; “Everything around it moves, as if just this one time and one time only, as if the message of Heraclitus has arrived here though some deep current, from the distance of an entire universe, in spite of all the senseless obstacles, because the water moves, it flows, it arrives, and cascades;...” The rhythm. The precision. The obsessive doubling and tripling and quadrupling back over scenes and images to put every detail in its perfect place; or at least, put details in places where they draw the eye of the reader so as to create an opportunity for mystery; an Acropolis whose hill you can climb but whose place you can never reach and then you get hit by a car.

The obsessiveness of Laszlo's prose naturally finds itself drawn to express obsessive actions, which, also pretty naturally, sets much of the action in Japan where precision is an end in itself. We see the restoration of a sacred Buddha statue, the carving of a Noh mask (I highly recommend Kissing the Mask by William Vollman, a critical study on Noh theater and femininity which could almost be read as a companion piece to Seiobo), and the cyclical rebuilding of a Shinto shrine and the ritual of cutting down the trees used to build it. But we also see the preparation of a panel for an altar in Renaissance Europe (which is insane), the construction of a Renaissance dowry box, and the copying of a legendary Andrei Rublev icon, all with such an intensity of precision that you are left feeling as though you have learned everything you could ever learn about the topic, while understanding nothing about it. (Oh, and a homeless guy buys a sharp knife in Barcelona, because reasons.)

This tension between knowledge and understanding, between erudition and meaning, between precision and communication reinforces the tension between the temporal experience of physically reading the book and unified experience it strives for. The movement about rebuilding the shrine climaxes when a native of Kyoto who had been acting as a guide for a Western journalist friend, hikes the friend to the top of a small mountain with a panoramic view of Kyoto at night. The Western journalist concludes the exact opposite of what his Japanese guide intended. Another way to describe Seiobo There Below is a symphony in words in opposition to the opposition to that moment of opposition. (Yeah, I'm going to go with that.) Or perhaps it just is and is about the impossibility of perfection. Or something else perfectly unified and perfectly divided.

Like Everything Matters! which is one of the most sincerely optimistic books I've ever read that also happens to be about the apocalypse, Seiobo There Below is one of the most sincerely cynical books I've ever read that also happens to be about beauty. It is a beautifully written obsession with beauty that finds at the end of its obsession...something that is not beauty. An empty box. The mask for a monster. A painting never completed. A very sharp knife purchased by a man who cannot afford it. The one time you don't look both ways before crossing the street. The relentless hollowness of ever lasting life. A long-legged raptor in a river.

Seiobo There Below is one of those absolutely brilliant, absolutely beautiful, absolutely stunning books, I have a difficult time recommending at the bookstore. For reasons I can totally understand, a lot of people simply will not or don't want to deal with sentences this long or feel they require an actual story arc to get into a book, or have a details limit after which something better fucking happen or they are totally tapping out. It's not a book you can put in a stranger's hands. But it is a beautiful book. And, in some ways, it is the most thorough and most direct study of beauty I've ever read. And if you have wondered about the process and statement of beauty, Seiobo There Below is a hill you should climb whether the “Acropolis” on top is the “Acropolis” in your mind or not.

Wednesday, October 30, 2013

The Best Books from the Indies Introduce Debut Panel

There was a huge range in quality in what I read for the panel. A few books were agonizing to reach the required 50 pages. A few I plowed through hoping for a surprising or at least interesting ending that I didn't get. As I mentioned in my previous post, a few started out fantastic only to lose their way, and not in the post-modern Pynchonesque characters wandering in the void of existence way of losing their way. And a few were fucking fantastic. Here are the two best books, according to me, from the panel reading.

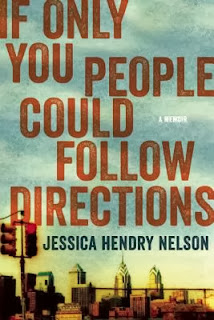

The Best Non-Fiction: If Only You People Could Follow Directions by Jessica Hendry Nelson (Coming out in January 2014)

My first thought when I started reading this book was: “Great, another addiction and dysfunction memoir, just what the world needs.” Though in many ways, Nelson's memoir is just that, she has made a narrative breakthrough that propelled her book to the top of the non-fiction heap. Rather than trying to jam the chaos of life into a chronological story-arc based narrative, Nelson explores her life through a series of essays that revolve around certain themes rather than certain times. Nelson bounces around in her life, she struggles with the ideas of her experiences and not just with the emotions of them, (though, also with the emotions of them) and through this has written a memoir that acts and feels like memory. Though the coping with addiction and dysfunction was compelling, the essay that convinced me of the depth of this book's value was “The Dollhouse,” in which she explores a very different kind of person.

Up till that essay, the book dealt with people we already knew from the genre of addiction and dysfunction memoir; the alcoholic father, the enabling mother, the brother following in the father's footsteps, and the troubled but charismatic best friend, but Cynthia, the focus of “The Dollhouse,” is an entirely different character. And though she is only the subject of one essay, she is as fully formed as any of the familiar characters in the book. That essay marks a thematic turning point in the book as afterward, Nelson explores more of her world outside of the dysfunctions she grew up with. We see her at a job in college, in New York, finding a partner, deciding to write, and finally, moving to Vermont where this collection was written and assembled. Which is not to say that everything in her life gets tied up in a neat little “struggle through strife to success package,” but that Nelson, despite how important the dysfunction was in her life can see and explore beyond it. Dysfunction is a part of her story, but not a part of her self.

There were a lot of typical ways Nelson could have presented the events in her life. The materials for the typical lurid memoir of drug, alcohol, and mental illness (probably) induced squalor are there. Instead, Nelson approached her life almost the way a critic would approach a work of literature; exploring the central themes, looking beyond the core characters, imagining other ways of being. Nelson has taken a genre that tends to be voyeur-bait and written a work of art. I hope more memoirists follow suit.

The Best Fiction: Faces in the Crowd by Valeria Luiselli (Coming out May 2014)

There are three narrative currents in Faces in the Crowd; the narrator living in Mexico City with her husband and children trying to write a novelization of poet Gilberto Owen's time in Harlem, the narrator remembering her time as a translator living in New York City that was the source of her idea for the novel, and the novel itself. Luiselli brilliantly weaves these currents together into a meditation on the nature of creation; not just creation of novels and poetry, but the creation of self and identity. The currents bleed into each other. Her husband reads over her shoulder. He leaves her or does not. Gilberto speaks in her prose. Translation hoax. Ghosts on the subway. The mix of fact and fiction both on the page and in the mind of the narrator.

One of the big weaknesses I saw in a number of the other books is the inability to differentiate character voices. Despite being different people, too often, different characters had the same narrative voice. In my own work, I've often found this process of differentiating voice the most difficult and time consuming part of the writing process. (see my earlier concerns about editing) In early drafts, all the characters sounded like me, in later drafts they all sounded like slightly different versions of me, rinse and repeat over the course of drafts (and years) until all of the characters had distinct, but not caricaturish, voices. So it is actually a fairly important demonstration of the bedrock quality of the work that the first-person voice of Gilberto Owen is very different from the first-person voice of the narrator describing her time in New York.

As a writer, I'm interested in how the author of a book earns my trust, how he or she proves to me the effort I'm going to put in to reading their book is going to be rewarded. For me, with Faces in the Crowd, it was the voice of the narrator's pre-school age son that earned my trust. Even more specifically, it was the word “workery,” the term the boy used to describe where his father went during the day, that showed me Luiselli was on to something. That one word demonstrates the character's playfulness, cleverness, and imagination and gives him an instant and recognizable voice. I dog-eared a dozen pages for brilliance. And in the end, we don't get a conclusion about the nature of poetry and identity, of authenticity and dishonesty, of art and self, but a moment of violent disruption that transfers the responsibility for further exploration from the narrator to the reader.

There were other good books in the pile for this panel, but these two blew the doors off everything else. Innovative. Sophisticated. Daring. Beautiful. I didn't know it at the beginning but If Only You People Could Follow Directions and Faces in the Crowd were exactly the kind of books I was hoping to discover this summer.

The Best Non-Fiction: If Only You People Could Follow Directions by Jessica Hendry Nelson (Coming out in January 2014)

My first thought when I started reading this book was: “Great, another addiction and dysfunction memoir, just what the world needs.” Though in many ways, Nelson's memoir is just that, she has made a narrative breakthrough that propelled her book to the top of the non-fiction heap. Rather than trying to jam the chaos of life into a chronological story-arc based narrative, Nelson explores her life through a series of essays that revolve around certain themes rather than certain times. Nelson bounces around in her life, she struggles with the ideas of her experiences and not just with the emotions of them, (though, also with the emotions of them) and through this has written a memoir that acts and feels like memory. Though the coping with addiction and dysfunction was compelling, the essay that convinced me of the depth of this book's value was “The Dollhouse,” in which she explores a very different kind of person.

Up till that essay, the book dealt with people we already knew from the genre of addiction and dysfunction memoir; the alcoholic father, the enabling mother, the brother following in the father's footsteps, and the troubled but charismatic best friend, but Cynthia, the focus of “The Dollhouse,” is an entirely different character. And though she is only the subject of one essay, she is as fully formed as any of the familiar characters in the book. That essay marks a thematic turning point in the book as afterward, Nelson explores more of her world outside of the dysfunctions she grew up with. We see her at a job in college, in New York, finding a partner, deciding to write, and finally, moving to Vermont where this collection was written and assembled. Which is not to say that everything in her life gets tied up in a neat little “struggle through strife to success package,” but that Nelson, despite how important the dysfunction was in her life can see and explore beyond it. Dysfunction is a part of her story, but not a part of her self.

There were a lot of typical ways Nelson could have presented the events in her life. The materials for the typical lurid memoir of drug, alcohol, and mental illness (probably) induced squalor are there. Instead, Nelson approached her life almost the way a critic would approach a work of literature; exploring the central themes, looking beyond the core characters, imagining other ways of being. Nelson has taken a genre that tends to be voyeur-bait and written a work of art. I hope more memoirists follow suit.

The Best Fiction: Faces in the Crowd by Valeria Luiselli (Coming out May 2014)

There are three narrative currents in Faces in the Crowd; the narrator living in Mexico City with her husband and children trying to write a novelization of poet Gilberto Owen's time in Harlem, the narrator remembering her time as a translator living in New York City that was the source of her idea for the novel, and the novel itself. Luiselli brilliantly weaves these currents together into a meditation on the nature of creation; not just creation of novels and poetry, but the creation of self and identity. The currents bleed into each other. Her husband reads over her shoulder. He leaves her or does not. Gilberto speaks in her prose. Translation hoax. Ghosts on the subway. The mix of fact and fiction both on the page and in the mind of the narrator.

One of the big weaknesses I saw in a number of the other books is the inability to differentiate character voices. Despite being different people, too often, different characters had the same narrative voice. In my own work, I've often found this process of differentiating voice the most difficult and time consuming part of the writing process. (see my earlier concerns about editing) In early drafts, all the characters sounded like me, in later drafts they all sounded like slightly different versions of me, rinse and repeat over the course of drafts (and years) until all of the characters had distinct, but not caricaturish, voices. So it is actually a fairly important demonstration of the bedrock quality of the work that the first-person voice of Gilberto Owen is very different from the first-person voice of the narrator describing her time in New York.

As a writer, I'm interested in how the author of a book earns my trust, how he or she proves to me the effort I'm going to put in to reading their book is going to be rewarded. For me, with Faces in the Crowd, it was the voice of the narrator's pre-school age son that earned my trust. Even more specifically, it was the word “workery,” the term the boy used to describe where his father went during the day, that showed me Luiselli was on to something. That one word demonstrates the character's playfulness, cleverness, and imagination and gives him an instant and recognizable voice. I dog-eared a dozen pages for brilliance. And in the end, we don't get a conclusion about the nature of poetry and identity, of authenticity and dishonesty, of art and self, but a moment of violent disruption that transfers the responsibility for further exploration from the narrator to the reader.

There were other good books in the pile for this panel, but these two blew the doors off everything else. Innovative. Sophisticated. Daring. Beautiful. I didn't know it at the beginning but If Only You People Could Follow Directions and Faces in the Crowd were exactly the kind of books I was hoping to discover this summer.

Wednesday, July 17, 2013

Another Post About Taipei

Near the end of her brilliant, Pulitzer Prize winning novel, A Visit from the Goon Squad, Jennifer Egan introduces the idea of “word casings.” Word casings are “words that no longer had meaning outside quotation marks. English was full of these empty words--'friend' and 'real' and 'story' and 'change'--words that had been shucked of their meanings and reduced to husks.” The quotation marks in words casings, at least as I interpret them, act as an indication that the enclosed word is beyond meaningful definition and that any usage of the word is a self-conscious application of an ersatz version of what was once an accepted and powerful idea. So the word casing “love” would mean something along the lines of: a feeling that matches enough of the characteristics of what people used to consider love, knowing that there is no stable meaning of love and the feeling I am describing to you as “love” may be totally different from what you would describe as “love.” Word casings are a potential natural progression of post-modernism that some would see as liberating and others as cynical.

Tao Lin ends his new novel Taipei with a word casing. After a drug experience makes him certain he has died, the protagonist Paul “heard himself say that he felt 'grateful to be alive.'” The passivity of the moment is breathtaking. Paul still didn't necessarily feel something but rather “heard himself say” that he felt something, and that something was not an actual feeling per se, but what he suspected had been defined as “'grateful to be alive'” back when we still had faith in the definitions of words like “grateful,” “alive,” and “to be.” Tao Lin's style is based on this profound passivity (more on that soon) but this moment takes it to a strange place. There is a chance that Paul, in his perpetual detachment, in his utter lack of ethical thought, in his drug use/abuse, and in his milieu of cynicism is most honest and meaningful in this moment with this word casing. There is a chance that, at this moment, the quotation marks aren't an avoidance of the effort of definition, aren't a cop out, aren't lazy irony, but are a vital to expression of the character's true self.

I often describe Tao Lin's writing as “autistic.” The actions are there but all of the emotional content has been stripped away from them. Another way to describe Tao Lin's style is as the logical conclusion of Heminway's anti-lyricism. The prose is only a dictation of what is said, done, and thought. It would be journalism, except journalism has at least some kind of commitment to cover statements and actions that are interesting, or, at the very least, relevant to a wide range of people. Lin, however, tends to write about someone like him. Even when not as directly autobiographical as Taipei seems to be, Lin's protagonists tend to be young male Asian-American writers living in New York. It's an unsettling, often unpleasant style. It rejects some of the basic agreements of literature. That said, though I can't say I “like” Tao Lin or “enjoy” reading him, there is something powerful about what he writes. He is doing something dramatic and different and cannot be ignored.

But there's something different about Taipei than his previous prose. Some barrier was broken, maybe with drugs or at least their depiction, and Lin's reportage style lead to some very un-jounalistic, un-Hemingway writing. Along with the basics of motion and the conversation (often painfully awkward), the narrator dictates Paul's thoughts and feelings, some of which are breathtaking and original. A few examples.

Really, nobody knows why we do what we do. We know the most recent reasons for our most recent actions, but the ultimate source of me typing these words at this moment is the same fundamental mystery of matter from energy or consciousness from matter or thoughts and emotions from consciousness. But we all have an illusion of the answer, an adequate understudy for the ultimate truth, an ersatz basis that allows us to continue doing. Paul is severed from the illusion of knowing what is going on in his life and why it is happening, and the cut itself is so clean, he doesn't even seem to realize it happened. Like everyone else, Paul just keeps moving, just keeps doing, saying, and thinking things, but unlike everyone else, he doesn't have a reason why. Lin has surgically removed it.

Sometimes the result of this surgery is excruciating. It is just agony every time Paul talks to anybody and my awkwardness is embarrassed whenever Paul talks with Erin about their relationship. And there is a lot of him just doing stuff. Just going to parties, just looking at the internet, just eating, just doing. There have been some vigorous, passionate, negative reactions to Taipei, and honestly, I can't blame those readers for hating this book. In some ways, by severing Paul from the basic illusion of human significance, Lin has severed his book from the joy of reading.

But then there are moments like those quoted above where Paul's intellect and imagination just take off. He imagines time. He imagines existence. He takes whatever boring, stupid, meaningless shit is happening around him and, without lying to himself about his value in existence, dresses it in the significance of lyrical metaphor and imagery. “Realizing this was only his concrete history, his trajectory through space-time from birth to death, he briefly imagined being able to click on his trajectory to access his private experience, enlarging the dot of the coordinate by shrinking, or zooming in, until it could be explored like a planet.” There is a process here, something I haven't pinned down, about meaning, that even if we don't enjoy, we should experience.

Literature is the laboratory of human experience. Just like science, literature only gets better if writers try everything, if writers take risks, if writers fail, and, just like science, you don't know who the Newton is until you know who the Newton is. Could it be Tao Lin? We'll only know when enough critics replicate his equation for gravity.

Tao Lin ends his new novel Taipei with a word casing. After a drug experience makes him certain he has died, the protagonist Paul “heard himself say that he felt 'grateful to be alive.'” The passivity of the moment is breathtaking. Paul still didn't necessarily feel something but rather “heard himself say” that he felt something, and that something was not an actual feeling per se, but what he suspected had been defined as “'grateful to be alive'” back when we still had faith in the definitions of words like “grateful,” “alive,” and “to be.” Tao Lin's style is based on this profound passivity (more on that soon) but this moment takes it to a strange place. There is a chance that Paul, in his perpetual detachment, in his utter lack of ethical thought, in his drug use/abuse, and in his milieu of cynicism is most honest and meaningful in this moment with this word casing. There is a chance that, at this moment, the quotation marks aren't an avoidance of the effort of definition, aren't a cop out, aren't lazy irony, but are a vital to expression of the character's true self.

I often describe Tao Lin's writing as “autistic.” The actions are there but all of the emotional content has been stripped away from them. Another way to describe Tao Lin's style is as the logical conclusion of Heminway's anti-lyricism. The prose is only a dictation of what is said, done, and thought. It would be journalism, except journalism has at least some kind of commitment to cover statements and actions that are interesting, or, at the very least, relevant to a wide range of people. Lin, however, tends to write about someone like him. Even when not as directly autobiographical as Taipei seems to be, Lin's protagonists tend to be young male Asian-American writers living in New York. It's an unsettling, often unpleasant style. It rejects some of the basic agreements of literature. That said, though I can't say I “like” Tao Lin or “enjoy” reading him, there is something powerful about what he writes. He is doing something dramatic and different and cannot be ignored.

But there's something different about Taipei than his previous prose. Some barrier was broken, maybe with drugs or at least their depiction, and Lin's reportage style lead to some very un-jounalistic, un-Hemingway writing. Along with the basics of motion and the conversation (often painfully awkward), the narrator dictates Paul's thoughts and feelings, some of which are breathtaking and original. A few examples.

The antlered, splashing, water-treading, land animal of his first consciousness would sink to some lower region, in the lake of himself, where he would sometimes descend in sleep and experience its disintegrating particles and furred pieces, brushing past, in dreams, as it disappeared into the patterns of the nearest functioning system.

Paul laid the side of his head on his arms, on the table, and closed his eyes. He didn't feel connected to a traceable series of linked events to a source that had purposefully conveyed him, from elsewhere, into this world. He felt like a digression that had forgotten from what it digressed and was continuing ahead in a kind of confused, choiceless searching. Fran and Daniel returned and ordered enchiladas, nachos. Paul ordered tequila, a salad, waffles with ice cream on top.

On the bus Erin slept with her head on Paul's lap...Paul stared at the lighted signs, most of which were off for the night, attached to almost every building to face oncoming traffic—animated and repeating like GIF files, or constant and glaring as exposed bulbs, from two-square rectangles like tiny wings to long strips like impressive Scrabble words with each square its own word, maybe too much information to convey to drivers—and sleepily though of how technology was no longer the source of wonderment and possibility it had been when, for example, he learned as a child at Epcot Center, Disney's future-themed 'amusement park,' that families of three, plus one robot maid and two robot dogs, would live in self-sustaining, transparent, deep-water spheres by something like 2004 or 2008. At some point, Paul vaguely realized, technology had, to him, begun to mostly only indicate the inevitability and vicinity of nothingness. Instead of postponing the nothingness on the other side of death by releasing nanobots into the bloodstream to fix things faster than they deteriorated...--technology seemed more likely to permanently eliminate life by uncontrollably fulfilling its only function: to indiscriminately convert matter, animate or inanimate, into computerized matter, for the purpose of increased converting power and efficiency, until the universe was one computer.

Really, nobody knows why we do what we do. We know the most recent reasons for our most recent actions, but the ultimate source of me typing these words at this moment is the same fundamental mystery of matter from energy or consciousness from matter or thoughts and emotions from consciousness. But we all have an illusion of the answer, an adequate understudy for the ultimate truth, an ersatz basis that allows us to continue doing. Paul is severed from the illusion of knowing what is going on in his life and why it is happening, and the cut itself is so clean, he doesn't even seem to realize it happened. Like everyone else, Paul just keeps moving, just keeps doing, saying, and thinking things, but unlike everyone else, he doesn't have a reason why. Lin has surgically removed it.

Sometimes the result of this surgery is excruciating. It is just agony every time Paul talks to anybody and my awkwardness is embarrassed whenever Paul talks with Erin about their relationship. And there is a lot of him just doing stuff. Just going to parties, just looking at the internet, just eating, just doing. There have been some vigorous, passionate, negative reactions to Taipei, and honestly, I can't blame those readers for hating this book. In some ways, by severing Paul from the basic illusion of human significance, Lin has severed his book from the joy of reading.

But then there are moments like those quoted above where Paul's intellect and imagination just take off. He imagines time. He imagines existence. He takes whatever boring, stupid, meaningless shit is happening around him and, without lying to himself about his value in existence, dresses it in the significance of lyrical metaphor and imagery. “Realizing this was only his concrete history, his trajectory through space-time from birth to death, he briefly imagined being able to click on his trajectory to access his private experience, enlarging the dot of the coordinate by shrinking, or zooming in, until it could be explored like a planet.” There is a process here, something I haven't pinned down, about meaning, that even if we don't enjoy, we should experience.

Literature is the laboratory of human experience. Just like science, literature only gets better if writers try everything, if writers take risks, if writers fail, and, just like science, you don't know who the Newton is until you know who the Newton is. Could it be Tao Lin? We'll only know when enough critics replicate his equation for gravity.

Wednesday, June 19, 2013

Review of In the House Upon the Dirt Between the Lake and the Woods

In the House Upon the Dirt Between the Lake and the Woods and the Woods exists in an old age; old because it happened long ago and old because it has been alive a long time, been many places and seen many things. It seeks the paradox of simple symbolism and meaninglessness of folk tales and legends, but with an awareness of all that has happened in storytelling in the last century or so. Like Jess Ball's The Way Through Doors, the works of Ludmilla Petrushevskaya, and a number of short stories by the famous and the less so, Matt Bell's novel taps into a growing trend of neo-folklore, stories and books using the rhythm, imagery, and events of folklore, myth, and legend to grapple with the chaotic, contradictory and confusing problems of modern living, subduing the mad complexity of an instant internet world into the simple images of campfire legends. This trend hasn't developed into a genre of its own yet, but it is one major commercial breakthrough from being a pop culture phenomenon. I don't know if In the House Upon the Dirt Between the Lake and the Woods will be that breakthrough, (Frankly, I have no fucking clue why some books break and others don't except when Oprah does it.) but it is an excellent novel, with an archetypal story and a powerful voice.

Two characteristics jumped out at me as I read. The first is the book's quiet brutality. With movies and video games we expect violence and brutality to be loud; gunshots, explosions, screams, the sound of breaking glass, mysterious engines revving out of sight of the victim strapped to a chair, folley-enhanced martial arts; but not all violence is loud. The narrator is a man, a fisherman and then later a trapper. The effect of his traps on the bodies of the animals he catches is related in clear and precise detail. Muscles are torn. Bones broken. Tendons snapped. Skin rent. The man fights a bear and every wound dealt and received is chronicled. There is decay and rot. Bodies break down. The man fights a squid and every wound dealt and received is chronicled. The man is torn apart by foundlings. He has a heart attack. His wife is burned beyond recognition. The bear smashes a foundling's skull. All in perfect detail but at a volume just above a whisper. It's an effect that could pass under your reading radar, but once I noticed, it was clear Bell's book belongs to the long tradition nature of red in tooth and claw narratives.

Second, is the distinctiveness of the voice itself. From the opening line, you can hear the voice in your head, like someone reading to you. The voice reminds me of good bourbon, how it can be smooth and biting at the same time, how it can be warm and give you shivers, how it has both comfort and desperation. But just like bourbon, if you like it you love it and if you don't you hate it. By definition, the distinctiveness of Bell's narrative voice will turn some readers away. If you don't like the voice, nothing in the plot or the character will redeem the book in your eyes. That is the risk of distinctive writing; on one edge, you break ground, excite imaginations, stretch capacities, and earn the respect of devoted readers and on the other edge, you cut your work off from swaths of the reading public. It is not hard to see why so many different books by so many different people all sound the same.

At its heart, this is a story about a man way, way over his head. The semi-nameless narrator (though it's never said, you can figure it out, or, at least I think I did.) just wants children with the wife he loves (figured out her name first) in the isolated house he made and to fish and trap for food until the day he dies. That's it. But everything around him is vastly more powerful; his wife who can sing things into being, the woods with its bear, the lake with its squid, the dirt, the ghosts, the moon, and when his wife creates a child from a bear cub because she was never able to carry a pregnancy to term, even that foundling is more powerful than the man. In an impulsive move, the man goes to kiss the small corpse of the first miscarriage (remember that quiet brutality thing) and swallows it instead and that being, called “the fingerling” is also more powerful in many ways than he is. And while we're at it, the man is selfish, short-sighted, and myopic. But he survives, and if survival itself does not equal power, it equals something like power, in that the man is always around to contribute, productively or destructively to all the surrounds him.